4 Lifelong and Relational Interculturality: Cultural Safety and Cultural Humility

Learning Objectives

By the time you have completed the content in this chapter, you should be equipped to:

- Define cultural safety and cultural humility

- Describe how these models support lifelong intercultural learning

- Explain why it is important to focus on relational aspects and the experience of those we interact with when evaluating intercultural effectiveness

Cultural Safety: The Impact of our Actions

The concept of cultural safety emerges from New Zealand and was first developed from considerations about inequal healthcare outcomes experienced by Māori people. Cultural safety has since expanded to various sectors including education, community services, and workplace settings (Williams, 1999). In its development, cultural safety is grounded in questions about why some communities, such as Indigenous peoples, have unequal and often negative outcomes when engaging with health care, education, and other social structures.

Cultural safety proposes that simply knowing information about culture is not enough to ensure effective interculturality. Rather, when we are engaging in intercultural relationships, cultural safety asks to think critically about inequalities, and how they are rooted in colonization and other unjust structures. When people engage in a process of learning to practice in culturally safe ways, we need to engage in self-reflection on our own cultural identities, and how social and cultural contexts shape the systems we are a part of (Ward et al., 2016).

Unlike cultural awareness or sensitivity, which are merely starting points, cultural safety represents an outcome determined by those receiving the service, focusing on whether they feel safe, respected, and able to express their cultural identity without judgment (Ward et al., 2016).

It is important to recognize that the cultural safety framework was developed in an Indigenous context and so is particularly relevant when we consider how we act in a good way in our relationship with Indigenous peoples.

Cultural Humility: A Framework for Intercultural Understanding

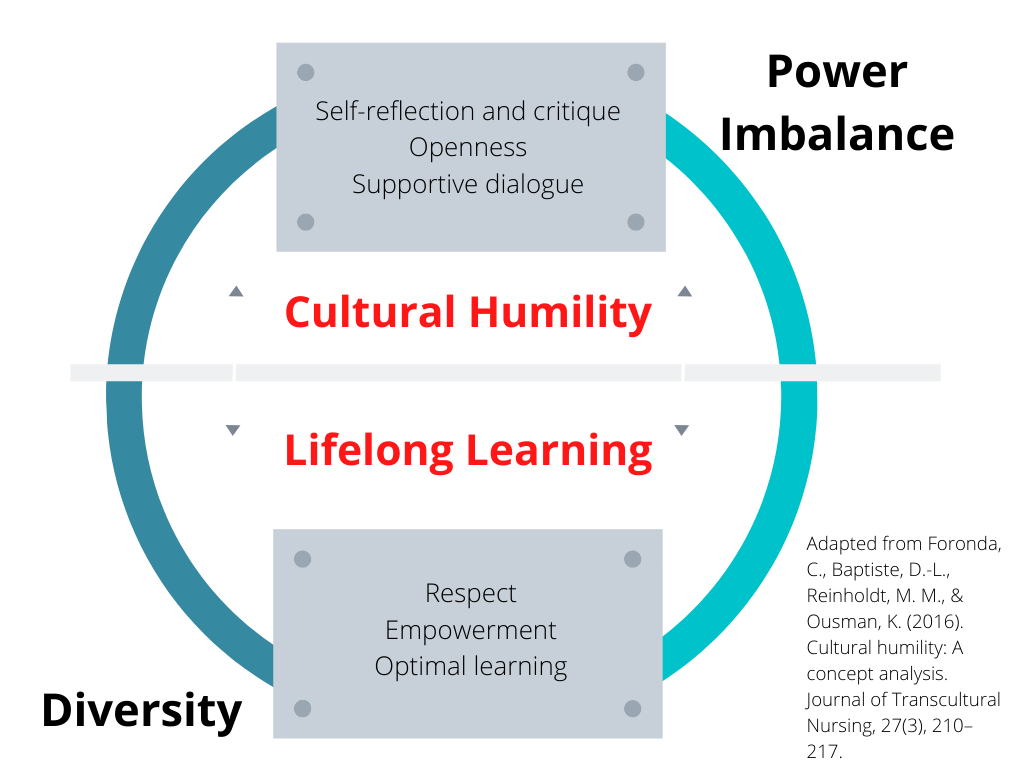

Cultural humility, introduced by Tervalon and Murray-Garcia (1998), provides university students with a valuable approach to understanding intercultural development as a relational process. Cultural humility “a process of openness, self-awareness, being egoless, and incorporating self-reflection and critique after willingly interacting with diverse individuals” (Foronda et al., 2016, p. 213). Rather than positioning cultural understanding as a skill or competency that we achieve, cultural humility frames it as an ongoing developmental journey. The idea of cultural humility aligns well with the idea of interculturality and its relational focus.

Cultural humility consists of several interconnected elements. Self-reflection requires examining one’s cultural background and inherent biases. Supportive dialogue involves engaging in meaningful conversations with individuals from different cultural backgrounds. Openness necessitates a willingness to acknowledge knowledge limitations and learn from others. When these elements work together, they foster environments characterized by mutual respect, empowerment, and optimal learning.

Although cultural humility discussions frequently appear in social work, healthcare, and counselling psychology literature, the approach is beneficial in any field where we interact with other people. The model emphasizes personal development through cultivating openness and genuine curiosity about others’ lived experiences. It highlights self-reflection as a crucial strategy for integrating experiences in ways that promote authentic growth. Furthermore, it emphasizes that interculturality requires dialogue and conversation within relationships. In other words, those who emphasize cultural humility are likely to believe that understanding cultural dimensions is not enough for effective intercultural relationships. Those who practice cultural humility would be cautious about making assumptions based on someone’s assumed national culture, and instead would prefer to ask questions and find out about the individual cultural identities of the person they are relating with.

A significant strength of cultural humility lies in its acknowledgment of power relationships that shape intercultural business encounters. These power dynamics are present both in societal inequalities between dominant and non-dominant cultural groups and in professional relationships within organizations. In corporate settings, cultural humility encourages examination of how leadership roles create power imbalances with employees, which inevitably influence workplace interactions and team dynamics. Leaders in organizations benefit from understanding how power operates in cross-cultural contexts. This knowledge supports the creation of psychologically safe environments where employees feel valued and empowered to contribute their authentic insights.

For university students developing professional identities, cultural humility offers a thoughtful framework that balances self-awareness with genuine openness to others’ experiences, creating a foundation for meaningful intercultural engagement throughout their academic and professional careers.

One critique of cultural humility is whether it should apply to those who are not from the dominant culture. For example, some who question cultural humility ask whether it is right to ask someone who experiences marginalization because of their race, disability, or other aspect of their identity to practice humility in relationships with others. These critics would state that cultural humility applies mostly to those with more power in an intercultural interaction.

Comparing Intercultural Competence, Cultural Humility, and Cultural Safety

When we think about cultural humility and cultural safety, it is helpful to think about how these approaches contrast with each other, and with competence-based models. The chart below compares cultural competence, cultural humility and cultural safety.

| Aspect | Cultural Competence | Cultural Safety | Cultural Humility |

| Definition | A range of cognitive, affective, behavioral, and linguistic skills that lead to effective and appropriate communication with people of other cultures (Deardorff, 2006) | An outcome based on respectful engagement that recognizes and strives to address power imbalances inherent in systems; determined by the person receiving care (Ward et al., 2016) | A process of self-reflection to understand personal and systemic biases, and to develop respectful relationships based on mutual trust (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998) |

| Primary Focus | Knowledge, skills, and behaviors to communicate effectively across cultures | Patient/client experience and feelings of safety; environment free of racism and discrimination | Self-reflection, lifelong learning, and acknowledging limitations of one’s cultural knowledge |

| Who Determines Success | Generally determined by the provider’s ability to demonstrate specific skills and knowledge | The recipient of services determines whether they feel culturally safe | Ongoing process without a specific endpoint; focuses on the journey rather than achievement |

| Power Dynamics | May acknowledge but less emphasis on systemic power differentials | Explicitly addresses power imbalances in healthcare and other systems | Focuses on dismantling power imbalances through self-awareness and humility |

| Learning Approach | Skills-based approach that can be taught and measured | Focuses on creating environments where people feel respected and empowered | Emphasizes lifelong learning and being a humble learner about others’ experiences |

| Historical Context | Developed from cross-cultural education and communication studies | Developed in New Zealand nursing education to address concerns of Māori students. | Emerged as a critique of the “mastery” implied in competence approaches |

| Key Components | Mindfulness, cognitive flexibility, tolerance for ambiguity, behavioral flexibility, cross-cultural empathy | Protection of cultural identity, focus on differences, understanding power dynamics in services | Self-reflection, addressing biases, lifelong learning, respectful engagement, acknowledging oneself as a learner |

Reflection Point

Review the comparison chart above. Consider how each perspective informs your understanding of your intercultural development.

- How does cultural competence inform your understanding of interculturality?

- How does the idea of cultural humility shape your understanding of how you show up in intercultural relationships?

- How does cultural safety help you to understand the limits of cultural competence and cultural humility?

Case Study

Review the case study below. What practices do you think illustrate effective cultural humility or cultural safety?

A Journey Toward Cultural Safety: Amir’s Story

The Internship

Amir, a final-year business student at a university in western Canada, arrived for his first day as a marketing intern at Horizon Community Development, a non-profit organization serving diverse immigrant communities. Though he had studied cross-cultural communication in his courses, this was his first opportunity to apply these concepts in a professional setting.

During the morning orientation, Sophia, the Marketing Director, briefed him on his first assignment: developing promotional materials for a financial literacy program aimed at recently arrived refugee families.

“We’ve struggled to get consistent participation from the South Sudanese community,” Sophia explained. “Our standard marketing approach hasn’t been effective. I’m hoping you can help us understand why and develop something more appropriate.”

The Initial Approach

Amir began by reviewing the existing promotional materials—sleek brochures featuring stock photos of smiling families in business attire looking at computer screens and smartphones.

Instead of immediately redesigning the materials based on his own assumptions, Amir asked Sophia if he could meet with members of the South Sudanese community to better understand their perspectives.

“That’s not our usual process for marketing materials,” Sophia said, looking surprised. “We typically design them in-house based on our program objectives.”

“I understand,” Amir replied. “But I believe we might develop more effective materials if we involve community members in the process.”

Building Relationships

Sophia arranged for Amir to meet with Nyamal, a respected figure in the South Sudanese community who occasionally collaborated with Horizon. When they met at a local coffee shop, Amir resisted the urge to immediately discuss the marketing project.

“Before we talk about the financial literacy program, I’d like to learn more about you and your community, if that’s alright,” Amir said.

Nyamal nodded appreciatively. Over the next hour, she shared stories about her journey to the country, the challenges her community faced, and their strengths and aspirations. Amir listened attentively, asking thoughtful questions and sharing relevant parts of his own experience as the child of immigrants.

“You know,” Nyamal said eventually, “most organizations just want to tell us what they think we need. They rarely take the time to understand who we are.”

Navigating Different Perspectives

When they finally discussed the financial literacy program, Amir asked, “What are your thoughts on the current program and how it’s being promoted?”

Nyamal explained that while the program content was valuable, several cultural barriers prevented participation. “In our community, financial discussions are considered private family matters. The brochures show individuals looking at screens alone, but our financial decisions are communal. Also, many in our community are more comfortable with oral communication than written materials.”

Amir nodded. “Thank you for sharing that. Would you feel comfortable telling me more about how financial knowledge is traditionally shared in your community?”

Nyamal appeared pleased by his question. “You’re the first person from Horizon who has asked about our own financial traditions rather than assuming we have none.”

Addressing Cultural Needs

Over the following weeks, Amir worked closely with Nyamal and other community members to develop new promotional strategies. They created visual materials featuring images of families and community groups rather than individuals, incorporated storytelling elements, and planned for community elders to introduce the program at cultural gatherings.

During a review meeting, Sophia questioned some of these approaches. “These materials don’t match our usual brand guidelines. And organizing community gatherings will take more resources than simply distributing brochures.”

“I understand your concerns,” Amir replied. “But based on what I’ve learned from community members, these approaches are more likely to resonate with their cultural values and communication preferences. The community members I’ve spoken with have expressed that they would feel more comfortable engaging with the program in these formats.”

Reflection and Feedback

Before finalizing the materials, Amir organized a feedback session with several South Sudanese community members.

“Do these materials feel respectful and appropriate to you?” he asked. “Would they make you more likely to participate in the program?”

“This is the first time an organization has shown our families accurately,” one participant commented. “You’ve represented our community values rather than just translating your materials into our language.”

Later that week, Amir reflected in his internship journal:

“Today I realized how easy it would have been to impose the organization’s standard marketing approach without considering cultural differences. I had to resist the pressure to prioritize brand consistency over cultural appropriateness. I’m aware that my business education has primarily focused on mainstream Western marketing models, and I need to continue learning about diverse cultural perspectives on financial matters. Most importantly, I learned that cultural safety isn’t about what I think is effective—it’s about whether community members feel respected and accurately represented in our communications.”

The Outcome

Two months later, the financial literacy program launched with the new promotional approach. Attendance from the South Sudanese community increased by 300% compared to previous programs. Nyamal later informed Amir that community members felt a sense of ownership in the program because they had been involved in shaping how it was presented.

“Whatever approach you took made a real difference,” Sophia acknowledged. “We’ve never seen this level of engagement before. I think we need to reconsider how we develop materials for all our diverse communities.”

Amir nodded, understanding that cultural safety wasn’t a one-time project but an ongoing process of listening, learning, and sharing power that would continue throughout his business career.

Conclusion

Cultural humility and cultural safety both work to help us understand that interculturality extends beyond self-development. We cannot consider ourselves to be interculturally effective without considering both our relationships with others and the social context we are working within. These models invite us to be particularly aware of when institutional power imbalances and historical inequalities influence our relationships.

Chapter References

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306287002

Foronda, C., Baptiste, D.-L., Reinholdt, M. M., & Ousman, K. (2016). Cultural humility: A concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(3), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677

Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

Ward, C., Branch, C., & Fridkin, A. (2016). What is Indigenous cultural safety—And why should I care about it? Visions Journal, 11(4), 29. https://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/visions/indigenous-people-vol11/what-indigenous-cultural-safety-and-why-should-i-care-about-it

Williams, R. (1999). Cultural safety—What does it mean for our work practice? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 213–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01240.x

AI Acknowledgement Statement: The comparison chart is adapted from content generated from Perplexity AI. (2025, May 21). Comparing cultural approaches in healthcare and education [AI-generated response]. Perplexity

The case study is generated from Perplexity AI. (2025, May 21). A journey toward cultural safety: Amir’s story [AI-generated case study]. https://www.perplexity.ai