Values as social structures

Section audio

In Chapter III, this textbook classified values as a social structure. You will recall that structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain action. How, exactly, do values enable certain actions while constraining others? The following sections will first consider values’ enabling nature, after which it will discuss how they constrain other actions.

Values Enable Action

Values enable action through at least two mechanisms. First, they motivate individuals to perform specific actions. Second, a social system’s current values will encourage people to perform activities consistent with those values.[1] Let’s consider each in turn.

Values Motivate action

Let’s look at an example from the case study in Appendix 1’s to see how values motivate action.

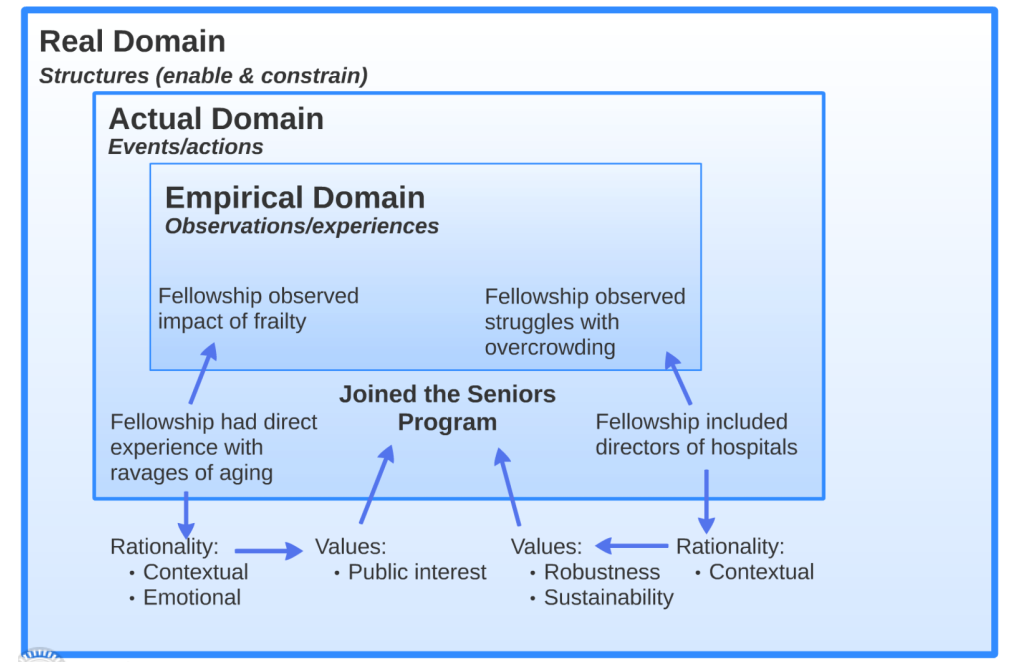

The fellowship responsible for developing and implementing the Seniors Program faced several hurdles. They had to spend countless hours reading literature and attending conferences to become experts in the field of delaying frailty. Though their CEO supported their efforts, many vice presidents and other senior executives did not.

This lack of vice-presidential support led to challenges in obtaining resources and personnel to do the work needed to implement the program. Later, when the fellowship wanted physicians to adopt the Seniors Program, they discovered that the doctors’ inability to bill for their work prevented them from taking up the program.

The fellowship managed all those challenges in addition to their regular duties as managers of a health authority. Their work on the Seniors Program was not a part of their daily job duties. They received no extra pay for their efforts. The fellowship volunteered to take on these tasks. Why?

A researcher interviewed the fellowship to learn what motivated them.[2] Without exception, several values drove members of the fellowship

The fellowship included many healthcare professionals who had worked extensively with senior citizens. Some of them had ageing parents with failing health. The members of the fellowship had seen first hand the ravages of frailty on the elderly.

When they discovered the Seniors Program had the potential to prevent frailty, they were deeply, passionately, committed to bringing the program to life. From the framework for public sector values presented in Chapter IV, the value of public interest drove these people.

Additionally, the members of the fellowship included the directors of hospitals. At the time, overcrowding plagued their hospitals. As the population of the surrounding region aged, they knew the demand for hospital resources would increase. They firmly believed the current healthcare system was unsustainable.

They reasoned that the longer they could keep senior citizens healthy, the less demand they would place on their hospitals. Using the public sector values framework, this line of reasoning implies values of robustness and sustainability.

Values define the ends we believe are worth pursuing and the means we find appropriate to achieve them. When a value touches you deeply, it motivates you to act.

By giving people the desire to act, values become enabling structures.[3] The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Values Provide Access to Resources Needed to Allow Action to Happen

The above example demonstrated how values motivate individuals. Organizations, however, also possess values of their own. Society creates hospitals, for example, to care for the sick and injured. That is, we create hospitals to pursue the value of public interest.

Recall from Chapter IV that organizations require a multiplicity of values to thrive. Though hospitals’ terminal value may be public interest, we want hospitals to have the capacity to manage the demand for services (value = robustness). We want hospitals not just today, but in the future, also (value = sustainability). We want new treatments to cure diseases that afflict us (value = innovation). And so on.

Thus, within the make-up of every organization is a set of values that guide its activities. Members of that organization will find it easier to take actions consistent with those values.

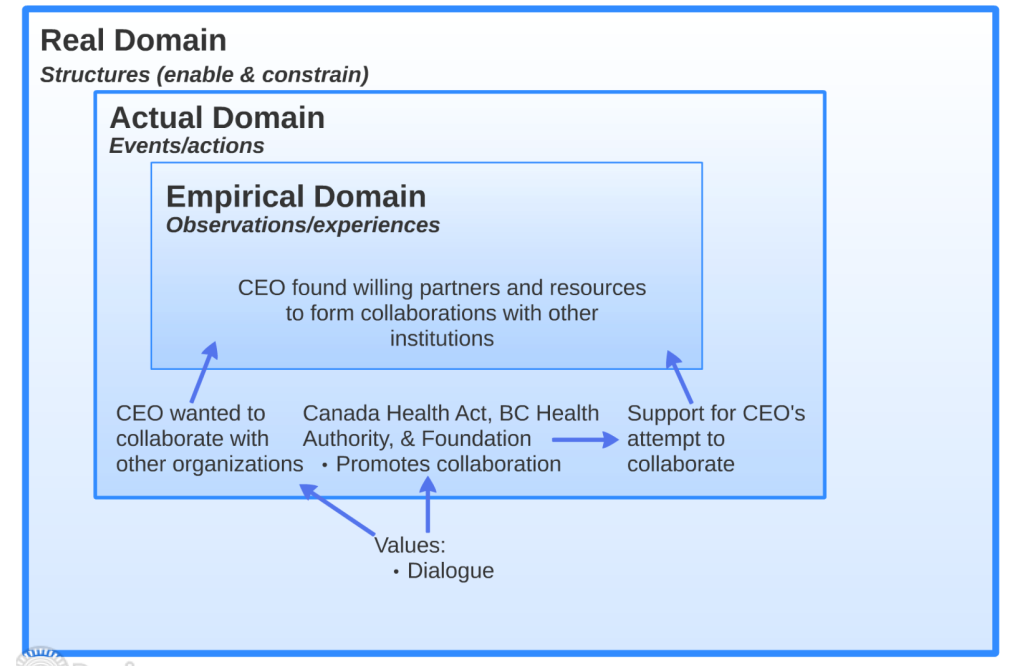

We can see an example of this with the Seniors Program. Recall that the CEO established the Seniors Program through a collaboration between health authorities in BC and Nova Scotia and the non-profit organization. These actions reflect the public sector value of dialogue and cooperativeness.

When you study the Canadian healthcare industry, you find these values are prominent. The Canada Health Act promotes collaboration among healthcare professionals.[4] Likewise, the mission statements of the BC Health Authority and the Foundation emphasized the importance of collaboration. The Foundation’s primary mandate was to foster partnerships between health authorities.

The commitment to work collectively was woven into the Canadian healthcare system. Thus, when the CEO wanted to collaborate, he found willing partners and resources to facilitate collective action.

The organization provides resources and helpful personnel to assist actions consistent with its values. In this way, values are enabling structures.[5] The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Values Constrain Action

In the same way that organizations foster actions consistent with their values, they restrict people’s ability to act in ways inconsistent with those values. These constraints may take at least two forms: active opposition versus passive lack of support.[6]

Values Lead to Active Opposition

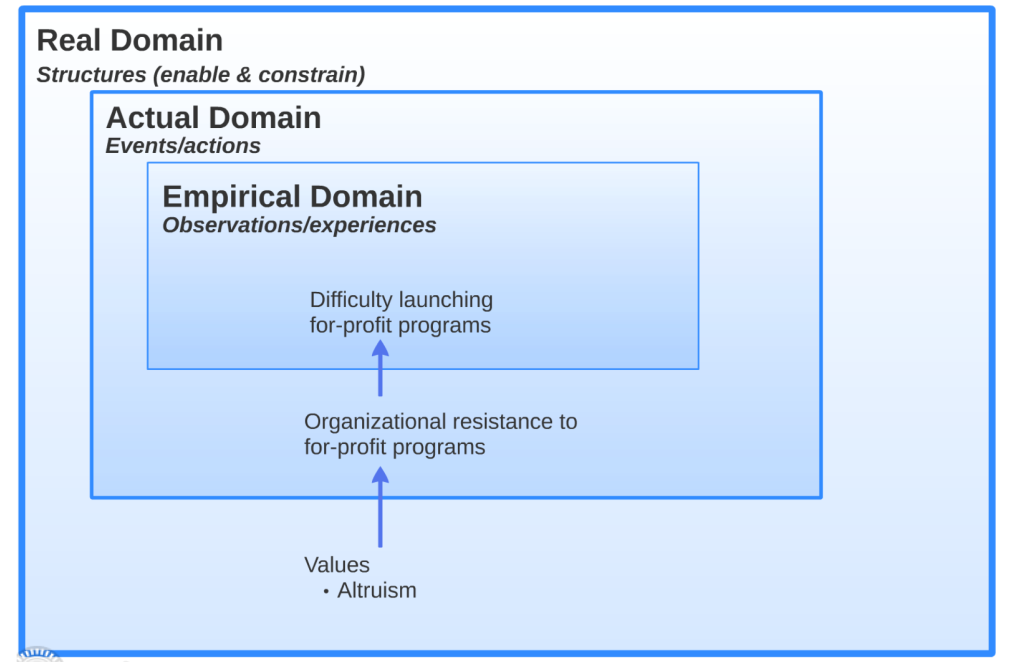

The Canadian healthcare system deeply honours equal access to all Canadian citizens regardless of their financial wellbeing. The idea that the healthcare system would deny services because someone was unable to afford them is anathema to Canadian culture. This attitude speaks to the public sector value of altruism.

Imagine, then, if the BC Health Authority CEO chose to establish the Seniors Program as a for-profit division. The healthcare system’s stakeholders would actively resist such an attempt. The BC government, which funds health authorities, would put pressure on the CEO to stop. Citizens and patient groups would actively challenge the CEO’s attempts to offer for-profit services. The CEO would likely lose their job and be unable to work in the Canadian healthcare sector.

If you act inconsistent with the organization’s values, then the organization will work to stop you. If the organization’s values are ingrained deeply enough, even the leader may lack the power to contradict them. In this way, values are constraining structures.[7] The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Values Lead to a Passive Lack of Support

An organization need not actively resist an action to constrain it. Refusing to provide resources needed to perform an act can snuff it out as effectively. The members of the fellowship working on the Seniors Program faced this problem.

The original intent of the people starting the Seniors Program was to create an innovation that would spread across Canada. This desire was reinforced as the results of this study demonstrated their ability to reduce frailty.

Yet, years after completing the study, the fellowship’s remaining members struggled to see their program adopted within their community. Spread outside of their community to the rest of Canada remained a distant dream. Why was this so?

Spreading innovation requires resources. You need personnel to promote the new idea. Other health regions need to be willing to take the risk of trying something new and suffering the disruption to the status quo as they integrate new activities. All of this costs time and money.

The provincial government provided funding to health authorities to administer healthcare inside their specific communities. Whereas the obligation for healthcare managers to use funding within their community was explicit, there was no mandate to use funds to spread innovations to other regions.

Thus, managers believed using their funds to spread innovations to other communities was a breach of their responsibility. This belief speaks to the value of accountability.

Though managers may see the Seniors Program’s importance, this sense of accountability constrained their ability to drive its wide-spread adoption. Starved of needed resources, attempts to spread the program floundered.

Even if an organization sees the desirability of action, its prevailing value system may constrain individuals’ ability to drive that action by denying them needed resources.

This denial of resources is not made purposefully to cause harm, but rather people prioritize other activities. In this way, values are constraining structures.[8] The figure below diagrams the above description using a critical realist framework.

Exercise: Can You Spot the Role of Power?

The above sections described how values enabled and constrained action. Review Chapter VI’s discussion of power.

- Using Lukes’ four-dimension framework of power, identify which dimensions of power individuals and organizations use to enable or constrain action in the above discussion.

- Using Fleming & Spicer’s framework on the faces and sites of power, identify the different faces and sites of power individuals and organizations use to enable or constrain action in the above discussion.

- Using the tactics of power identified by Flyvbjerg, identify the different tactics of power that people and organizations use to enable or constrain action in the above discussion.

Key Takeaways

- Values enable by motivating action

- Values enable by providing access to resources needed to allow actions to happen.

- Values constrain by creating active resistance.

- Values constrain by creating passive lack of support.

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Government of Canada. (2014, July 26). Canada Health Act: R.S.C., 1985, c. C-6. Retrieved from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-6/page-1.html ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

- Anderson, B. C. (2019). Values, Rationality, and Power: Developing Organizational Wisdom--A Case Study of a Canadian Healthcare Authority. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↵

In the critical realist framework, social structures are forces in social settings that enable or constrain the actions people can take.

Terminal values are those values pursued as ends in themselves.