Types of Communication and Channels

8.2 Different Types of Communication and Channels

Types of Communication

There are three types of communication including: verbal communication involving listening to a person to understand the meaning of a message, written communication, in which a message is read; and nonverbal communication, involving observing a person and inferring meaning. Let’s start with verbal communication, which is the most common form of communication.

Verbal Communication

Verbal communications in business take place over the phone or in person. The medium of the message is oral. Let’s return to our printer cartridge example. This time, the message is being conveyed from the sender (the manager) to the receiver (an employee named Bill) by telephone. We’ve already seen how the manager’s request to Bill (“Buy more printer toner cartridges!”) can go awry. Now let’s look at how the same message can travel successfully from sender to receiver.

Manager (speaking on the phone): “Good morning Bill!”

(By using the employee’s name, the manager is establishing a clear, personal link to the receiver.) Manager: “Your division’s numbers are looking great.”

(The manager’s recognition of Bill’s role in a winning team further personalizes and emotionalizes the conversation.)

Manager: “Our next step is to order more printer toner cartridges. Would you place an order for 1,000 printer toner cartridges with Jones Computer Supplies? Our budget for this purchase is $30,000, and the printer toner cartridges need to be here by Wednesday afternoon.” (The manager breaks down the task into several steps. Each step consists of a specific task, time frame, quantity, or goal.)

Bill: “Sure thing! I’ll call Jones Computer Supplies and order 1,000 more printer toner cartridges, not exceeding a total of $30,000, to be here by Wednesday afternoon.”

(Bill, a model employee, repeats what he has heard. This is the feedback portion of the communication. Feedback helps him recognize any confusion he may have had hearing the manager’s message. Feedback also helps the manager hear if she has communicated the message correctly.)

Storytelling is an effective form of verbal communication that serves an important organizational function by helping to construct common meanings for individuals within the organization. Stories can help clarify key values and also help demonstrate how certain tasks are performed within an organization. Story frequency, strength, and tone are related to higher organizational commitment (McCarthy, 2008). The quality of the stories is related to the ability of entrepreneurs to secure capital for their firms (Martens, Jennings, & Devereaux, 2007).

While the process may be the same, high-stakes communications require more planning, reflection, and skill than normal day-to-day interactions at work. Examples of high-stakes communication events include asking for a raise or presenting a business plan to a venture capitalist. In addition to these events, there are also many times in our professional lives when we have crucial conversations, which are defined as discussions in which not only are the stakes high, but also the opinions vary. Emotions run strong (Patterson et al., 2002). One of the most consistent recommendations from communications experts is to work toward using “and” instead of “but” when communicating under these circumstances. In addition, be aware of your communication style and practice being flexible; it is under stressful situations that communication styles can become the most rigid.

OB Toolbox: 8 Recommendations for Improving the Quality of Your Conversations

- Be the first to say hello. Use your name in your introduction, in case others have forgotten it.

- Think before you speak. Our impulse is often to imitate movies by offering fast, witty replies in conversation. In the real world, a careful silence can make us sound more intelligent and prevent mistakes.

- Be receptive to new ideas. If you disagree with another person’s opinion, saying, “Tell me more,” can be a more useful way of moving forward than saying, “That’s stupid!”

- Repeat someone’s name to yourself and then aloud, when being introduced. The form of the name you use may vary. First names work with peers. Mr. or Ms. is common when meeting superiors in business.

- Ask questions. This establishes your interest in another person.

- Listen as much, if not more, than you speak. This allows you to learn new information.

- Use eye contact. Eye contact shows that you are engaged. Also, be sure to smile and make sure your body language matches your message.

- Mirror the other person. Occasionally repeat what they’ve said in your own words. “You mean ” (Fine, 2005; Gabor, 1983).

Written Communication

In contrast to oral and verbal communications, written business communications are printed messages. Examples of written communications include memos, proposals, e-mails, letters, training manuals, and operating policies. They may be printed on paper or appear on the screen. Written communication is often asynchronous. That is, the sender can write a message that the receiver can read at any time, unlike a conversation that is carried on in real-time. Written communication can also be read by many people (such as all employees in a department or all customers). It’s a “one-to-many” communication, as opposed to a one-to-one conversation. There are exceptions, of course: A voicemail is an oral message that is asynchronous. Conference calls and speeches are oral one-to-many communications, and e-mails can have only one recipient or many.

Normally, verbal communication takes place in real-time. Written communication, by contrast, can be constructed over a longer period of time. It also can be collaborative. Multiple people can contribute to the content of one document before that document is sent to the intended audience.

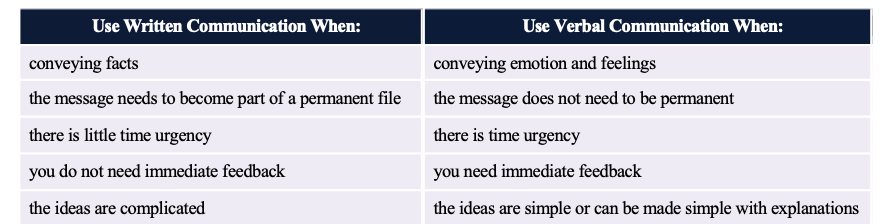

Verbal and written communications have different strengths and weaknesses. In business, the decision to communicate verbally or in written form can be a powerful one. As we’ll see below, each style of communication has particular strengths and pitfalls. When determining whether to communicate verbally or in writing, ask yourself: Do I want to convey facts or feelings? Verbal communications are a better way to convey feelings. Written communications do a better job of conveying facts.

Picture a manager making a speech to a team of 20 employees. The manager is speaking at a normal pace. The employees appear interested. But how much information is being transmitted? Probably not as much as the speaker believes. The fact is that humans listen much faster than they speak. The average public speaker communicates at a speed of about 125 words a minute, and that pace sounds fine to the audience. (In fact, anything faster than that probably would sound unusual. To put that figure in perspective, someone having an excited conversation speaks at about 150 words a minute.) Based on these numbers, we could assume that the audience has more than enough time to take in each word the speaker delivers, which creates a problem. The average person in the audience can hear 400 to 500 words a minute (Lee & Hatesohl). The audience has more than enough time to hear. As a result, their minds may wander.

As you can see, oral communication is the most often used form of communication, but it is also an inherently flawed medium for conveying specific facts. Listeners’ minds wander. It’s nothing personal—in fact, it’s a completely normal psychological occurrence. In business, once we understand this fact, we can make more intelligent communication choices based on the kind of information we want to convey.

Nonverbal Communication

What you say is a vital part of any communication. Surprisingly, what you don’t say can be even more important. Research shows that nonverbal cues can also affect whether or not you get a job offer. Judges examining videotapes of actual applicants were able to assess the social skills of job candidates with the sound turned off. They watched the rate of gesturing, time spent talking, and formality of dress to determine which candidates would be the most socially successful on the job (Gifford, Ng, & Wilkinson, 1985). Research also shows that 55% of in-person communication comes from nonverbal cues such as facial expressions, body stances, and tone of voice. According to one study, only 7% of a receiver’s comprehension of a message is based on the sender’s actual words, 38% is based on paralanguage (the tone, pace, and volume of speech), and 55% is based on nonverbal cues (body language) (Mehrabian, 1981). To be effective communicators, our body language, appearance, and tone must align with the words we’re trying to convey. Research shows that when individuals are lying, they are more likely to blink more frequently, shift their weight, and shrug (Siegman, 1985).

A different tone can change the perceived meaning of a message. For example, imagine that you’re a customer interested in opening a new bank account. At one bank, the bank officer is dressed neatly. She looks you in the eye when she speaks. Her tone is friendly. Her words are easy to understand yet professional sounding. “Thank you for considering Bank of the East Coast. We appreciate this opportunity and would love to explore ways that we can work together to help your business grow,” she says with a friendly smile. At the second bank, the bank officer’s tie is stained. He looks over your head and down at his desk as he speaks. He shifts in his seat and fidgets with his hands. His words say, “Thank you for considering Bank of the West Coast. We appreciate this opportunity and would love to explore ways that we can work together to help your business grow,” but he mumbles his words, and his voice conveys no enthusiasm or warmth. Which bank would you choose? The speaker’s body language must match his or her words. If a sender’s words and body language don’t match—if a sender smiles while telling a sad tale, for example—the mismatch between verbal and nonverbal cues can cause a receiver to dislike the sender actively.

Following are a few examples of nonverbal cues that can support or detract from a sender’s message.

Body Language

A simple rule of thumb is that simplicity, directness, and warmth convey sincerity. Sincerity is vital for effective communication. In some cultures, a firm handshake, given with a warm, dry hand, is a great way to establish trust. A weak, clammy handshake might convey a lack of trustworthiness. Gnawing one’s lip conveys uncertainty. A direct smile conveys confidence.

Newly conducted research by Amy Cuddy (2012) from Harvard University has found that not only can body language impact others’ perception of us, but it can also impact our own perception of ourselves! This Ted Talk below describes the research and the outcome: https://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are?language=en

Eye Contact

In business, the style and duration of eye contact vary greatly across cultures. In the United States, looking someone in the eye (for about a second) is considered a sign of trustworthiness.

Facial Expressions

The human face can produce thousands of different expressions. Experts have decoded these expressions as corresponding to hundreds of different emotional states (Ekman, Friesen, & Hager, 2008). Our faces convey basic information to the outside world. Happiness is associated with an upturned mouth and slightly closed eyes; fear with an open mouth and wide-eyed stare. Shifty eyes and pursed lips convey a lack of trustworthiness. The impact of facial expressions in conversation is instantaneous. Our brains may register them as “a feeling” about someone’s character. For this reason, it is important to consider how we appear in business as well as what we say. The muscles of our faces convey our emotions. We can send a silent message without saying a word. A change in facial expression can change our emotional state. Before an interview, for example, if we focus on feeling confident, our face will convey that confidence to an interviewer. Adopting a smile (even if we’re feeling stressed) can reduce the body’s stress levels.

Posture

The position of our body relative to a chair or other person is another powerful silent messenger that conveys interest, aloofness, professionalism, or lack thereof. Head up, back straight (but not rigid) implies an upright character. In interview situations, experts advise mirroring an interviewer’s tendency to lean in and settle back in a seat. The subtle repetition of the other person’s posture conveys that we are listening and responding.

Touch

The meaning of a simple touch differs between individuals, genders, and cultures. In Mexico, when doing business, men may find themselves being grasped on the arm by another man. To pull away is seen as rude. In Indonesia, to touch anyone on the head or to touch anything with one’s foot is considered highly offensive. In the Far East and some parts of Asia, according to business etiquette writer Nazir Daud, “It is considered impolite for a woman to shake a man’s hand” (Daud, 2008). Americans, as we have noted above, place great value in a firm handshake. But handshaking as a competitive sport (“the bone-crusher”) can come off as needlessly aggressive both at home and abroad.

Communication Channels

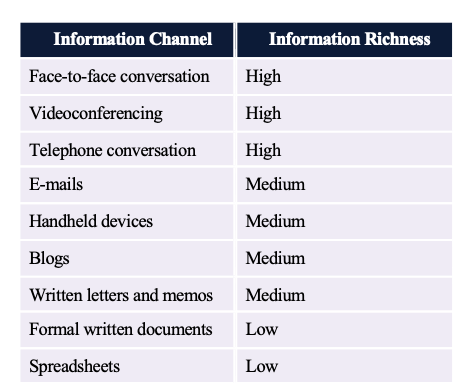

The channel, or medium, used to communicate a message affects how accurately the message will be received. Channels vary in their “information-richness.” Information-rich channels convey more non-verbal information. Research shows that effective managers tend to use more information-rich communication channels than less effective managers (Allen & Griffeth, 1997; Yates & Orlikowski, 1992). The figure below illustrates the information richness of different channels.

The key to effective communication is to match the communication channel with the goal of the message (Barry & Fulmer, 2004). For example, written media may be a better choice when the sender wants a record of the content, has less urgency for a response, is physically separated from the receiver, and doesn’t require a lot of feedback from the receiver or when the message is complicated and may take some time to understand.

Oral communication, on the other hand, makes more sense when the sender is conveying a sensitive or emotional message, needs feedback immediately, and does not need a permanent record of the conversation.

Like face-to-face and telephone conversations, videoconferencing has high information richness, because receivers and senders can see or hear beyond just the words that are used—they can see the sender’s body language or hear the tone of their voice. Handheld devices, blogs, written letters, and memos offer medium-rich channels because they convey words and pictures or photos. Formal written documents, such as legal documents and budget spreadsheets, convey the least richness because the format is often rigid and standardized. As a result, the tone of the message is often lost.

The growth of e-mail has been spectacular, but it has also created challenges in managing information and increasing the speed of doing business. Over 100 million adults in the United States use e-mail at least once a day (Taylor, 2002). Internet users around the world send an estimated 60 billion e-mails each day, and a large portion of these are spam or scam attempts (60 Billion emails sent daily worldwide, 2006). That makes e-mail the second most popular medium of communication worldwide, second only to voice. Less than 1% of all written human communications even reach paper these days (Isom, 2008). To combat the overuse of e-mail, companies such as Intel have even instituted “no e-mail Fridays.” During these times, all communication is done via other communication channels. Learning to be more effective in your e-mail communications is an important skill. To learn more, check out the OB Toolbox on business e-mail do’s and don’ts.

OB Toolbox: Business email “dos and don’ts”

- DON’T send or forward chain e-mails.

- DON’T put anything in an e-mail that you don’t want the world to see.

- DON’T write a message in capital letters-this is the equivalent of SHOUTING.

- DON’T routinely CC everyone. Reducing inbox clutter is a great way to increase communication.

- 5. DON’T hit send until you’ ve spell-checked your e-mail.

- DO use a subject line that summarizes your message, adjusting it as the message changes over time.

- DO make your request in the first line of your e-mail. (And if that’s all you need to say, stop there!)

- DO end your e-mail with a brief sign-off such as, “Thank you,” followed by your name and contact information.

- DO think of a work e-mail as a binding communication.

- DO let others know if you’ve received an e-mail in error (Kawasaki, 2006; Leland, 2000).

You might feel uncomfortable conveying an emotionally laden message verbally, especially when the message contains unwanted news. Sending an e-mail to your staff that there will be no bonuses this year may seem easier than breaking the bad news face-to-face, but that doesn’t mean that e-mail is an effective or appropriate way to break this kind of news. When the message is emotional, the sender should use verbal communication. Indeed, a good rule of thumb is that more emotionally laden messages require more thought in the choice of channel and how they are communicated.

Cross-Cultural Communication

Culture is a shared set of beliefs and experiences common to people in a specific setting. The setting that creates a culture can be geographic, religious, or professional. As you might guess, the same individual can be a member of many cultures, all of which may play a part in the interpretation of certain words.

The different and often “multicultural” identity of individuals in the same organization can lead to some unexpected and potentially large miscommunications. For example, during the Cold War, Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev told the American delegation at the United Nations, “We will bury you!” His words were interpreted as a threat of nuclear annihilation. However, a more accurate reading of Khruschev’s words would have been, “We will overtake you,” meaning economic superiority. The words, as well as the fear and suspicion that the West had of the Soviet Union at the time, led to a more alarmist and sinister interpretation (Garner, 2007).

Miscommunications can arise between individuals of the same culture as well. Many words in the English language mean different things to different people. Words can be misunderstood if the sender and receiver do not share common experiences. A sender’s words cannot communicate the desired meaning if the receiver has not had some experience with the objects or concepts the words describe (Effective communication, 2004).

It is particularly important to keep this fact in mind when you are communicating with individuals who may not speak English as a first language. For example, when speaking with non-native English-speaking colleagues, avoid “isn’t it?” questions. This sentence construction does not exist in many other languages and can be confusing for non-native English speakers. For example, to the question, “You are coming, aren’t you?” they may answer, “Yes” (I am coming) or “No” (I am coming), depending on how they interpret the question (Lifland, 2006).

Cultures also vary in terms of the desired amount of situational context related to interpreting situations. People in very high-context cultures put a high value on establishing relationships before working with others and tend to take longer to negotiate deals. Examples of high-context cultures include China, Korea, and Japan. Conversely, people in low-context cultures “get down to business” and tend to negotiate quickly. Examples of low-context cultures include Germany, Scandinavia, and the United States (Hall, 1976; Munter, 1993).

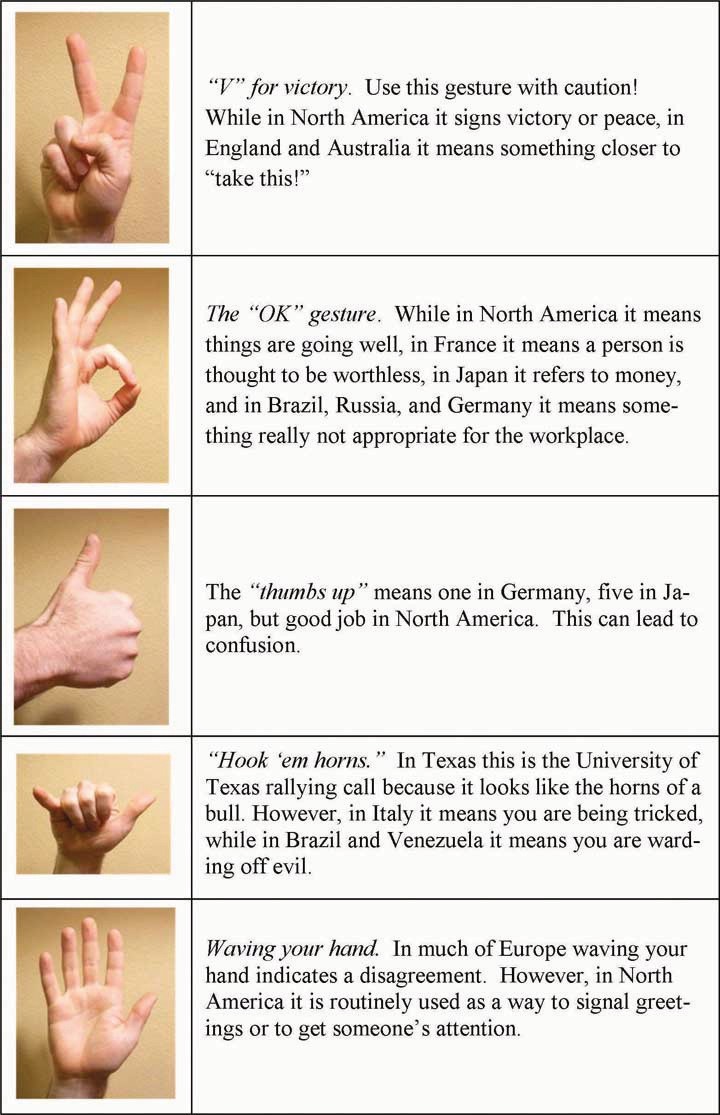

Finally, don’t forget the role of nonverbal communication. As we learned in the nonverbal communication section, in the United States, looking someone in the eye when talking is considered a sign of trustworthiness. In China, by contrast, a lack of eye contact conveys respect. A recruiting agency that places English teachers warns prospective teachers that something that works well in one culture can offend in another: “In Western countries, one expects to maintain eye contact when we talk with people. This is a norm we consider basic and essential. This is not the case among the Chinese. On the contrary, because of the more authoritarian nature of the Chinese society, steady eye contact is viewed as inappropriate, especially when subordinates talk with their superiors” (Chinese culture-differences and taboos).

It’s easy to see how meaning could become confused, depending on how and when these signals are used. When in doubt, experts recommend that you ask someone around you to help you interpret the meaning of different gestures, that you be sensitive, and that you remain observant when dealing with a culture different from your own.

Exercises

1. How can you assess if you are engaging in ethical communications?

2. What experiences have you had with cross-cultural communications? Please share at least one experience when it has gone well and one when it has not gone well.

3. What advice would you give to someone who will be managing a new division of a company in another culture in terms of communication?

Communication in a Virtual Work Environment With New Technologies

Covid-19 has revolutionized the way we work and communicate with others while working. Remote work has had a significant impact on workplace communication, both positively and negatively, in some of the following ways:

- Increase in digital communication: With remote work, there has been a significant increase in the use of digital communication tools such as email, instant messaging, video conferencing, and project management software. These tools allow employees to communicate and collaborate effectively regardless of their location.

- Flexibility: Remote work has also allowed for greater flexibility in communication. Employees can choose the communication tools that work best for them, and they can communicate at times that are most convenient for them.

- Lack of nonverbal cues: One of the challenges of remote work is the lack of nonverbal cues. When communicating digitally, it can be challenging to pick up on facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice. This can lead to misinterpretation and misunderstandings.

- The increased importance of written communication skills: With the rise in digital communication, written communication skills have become more critical than ever. Employees need to be able to write clearly and effectively to avoid misunderstandings and confusion.

- Need for intentional communication: With remote work, communication needs to be intentional. Managers need to be more deliberate in communicating with their team members, and employees need to be more intentional in seeking out communication when they need it.

- More Asynchronous Communication: Remote work has allowed for more asynchronous communication, where people can communicate with each other at different times. For example, someone can send an email or a message outside of work hours, and the recipient can respond later.

- Increased Importance of Clear Communication: With remote work, there is a greater need for clear communication. Misunderstandings can arise more easily when people are not face-to-face, so it’s important to be clear in our writing and make sure we understand each other.

- Increased Use of Video Conferencing: Video conferencing has become more popular as remote work has become more common. This allows people to have face-to-face interactions without being in the same room, which can help build better relationships among colleagues.

Overall, remote work has had a significant impact on workplace communication. While there are some challenges, there are also many benefits to remote communication, such as increased flexibility and access to digital tools.

Not only has remote work significantly changed the way we communicate, but the increased adoption of new technologies such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, SharePoint, and even Ai Software such as Chat GPT has revolutionized how we communicate. It may be of interest to note that the above list of ways in which remote work has changed our communication at work was generated by Chat GPT! https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt

The adoption of Ai technology exploded in 2022, with the release of platforms such as Chat GPT changing the world of communication forever. Funk (2023) explains the benefits and challenges of Ai technology as follows (p2):

The Benefits of AI in Communication

Ability to improve accessibility and efficiency. For example, chatbots and virtual assistants can provide instant responses to inquiries and customer service requests, freeing up human customer service agents to focus on more complex tasks. AI-powered translation services can also break down language barriers and facilitate communication between individuals who speak different languages.

Enhance the personalization of communication. With access to large amounts of data, AI-powered tools can analyze user behavior and preferences, tailoring communication to suit the individual’s needs. Additionally, AI can use predictive capabilities to anticipate what a user may need or want, providing suggestions and recommendations that can enhance the user’s experience. For example, Spotify uses AI to curate personalized playlists for its users, based on their listening history and preferences.

Ability to analyze and interpret large amounts of data. This provides insights that can help individuals and organizations make more informed decisions. For example, social media monitoring tools can use AI to analyze trends and sentiment across social media platforms, helping businesses to better understand their audience and improve their marketing strategies.

The Challenges and Risks of AI in Communication

Difficultly to differentiate between AI-generated and human-generated communication. For example, as AI becomes more sophisticated, it may be more difficult to differentiate between text written by a computer versus a human. This could lead to issues with trust and transparency, particularly in areas such as journalism and marketing.

Increased Bias. AI algorithms may perpetuate biases and reinforce existing inequalities if they are not properly designed and tested. Research has shown that AI language models can perpetuate gender and racial biases, reflecting the biases that are present in the data they are trained on. For example, a study by the AI Now Institute found that popular language models such as GPT-2, 3, 4 and BERT have gender biases, with male pronouns and names being more frequently associated with career-related words than female pronouns and names.

Communication Among Neurodiverse Individuals

An increasing amount of research is being conducted examining the role of communication among neurodiverse individuals. To encourage sustainable growth, many bet performing companies are looking to identify new talent and have found that neurodiverse individuals — those with autism, Asperger’s syndrome, dyslexia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and dyspraxia — can create innovation and contribute to the skills needed for emerging areas such as artificial intelligence, automation, blockchain, cybersecurity and data management (Twaronite, 2020). Over 15% of the Canadian workforce is neurodiverse, and leveraging the unique capabilities of these employees is becoming a competitive advantage among organizations (Bitti, 2022). Leveraging the unique talents of neurodiverse individuals involves having an environment that encourages open and clear communication for all team members to connect with leaders, colleagues, and each other. Specifically, Twaronite (2020) recommends that workplaces:

- Communicate using straightforward language. Neurodiverse employees are more often likely to take communication at face value. Therefore, avoiding sarcasm and expressions that may be misunderstood or misinterpreted can go a long way. Neurodiverse colleagues will understand you more easily if you state your emotions and ask specific questions rather than open-ended ones.

- Embrace honesty. Individuals on the autism spectrum typically speak with complete honesty, and their frankness can sometimes be incorrectly mistaken for rudeness. It’s important to reflect and understand that these comments often stem from individuals coping with the stress of sensory overload. Finding ways to work with and embrace different communication styles can help make certain everyone feels like they have a voice at the table.

- Pace the flow of information. Our neurodiverse colleagues have made invaluable contributions to our organization because of their technologically inclined and detail-oriented abilities, along with their strong skills in analytics, mathematics, pattern recognition, and information processes. However, when others communicate facts, data, and other information, it should be done so in a logical and ordered sequence to avoid information overload. Also, remember the power of the pause — allow for rest and recovery time in between sharing information — to give your team members more time to process what has been said.

- Be mindful of sensitivities. At times, individuals on the spectrum may be disconcerted by sounds, sights, and movement. Changes in routine or personnel, such as having to work remotely abruptly, can take some time for neurodiverse individuals to adjust. When communicating about changes, be patient and allow extra time for them to adapt. (p.2)

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have reviewed why effective communication matters to organizations. Communication may break down as a result of many communication barriers that may be attributed to the sender or receiver. Therefore, effective communication requires familiarity with the barriers. Choosing the right channel for communication is also important because choosing the wrong medium undermines the message. When communication occurs in a cross-cultural context, extra caution is needed, given that different cultures have different norms regarding nonverbal communication, and different words will be interpreted differently across cultures. By being sensitive to the errors outlined in this chapter and adopting active listening skills, you may increase your communication effectiveness.