Cultural Diversity

10.5 Cultural Diversity

Culture refers to values, beliefs, and customs that exist in a society. In the United States, the workforce is becoming increasingly multicultural, with close to 16% of all employees being born outside the country. In addition, the world of work is becoming increasingly international. The world is going through a transformation in which China, India, and Brazil are emerging as major players in world economics. Companies are realizing that doing international business provides access to raw materials, resources, and a wider customer base. For many companies, international business is where most of the profits lie, such as for Apple Inc. In the second quarter of fiscal year 2021, around 67 percent of Apple Inc’s revenue was generated outside of the United States.

International companies are also becoming major players with foreign investors. Originally a Swedish company, Spotify now has headquarters in multiple areas across the globe including New York City. While its CEO and founder holds a large percentage of the company, Chinese investor Tencent Holdings Limited LLC bought 10% of the company back in 2017 while Spotify bought 10% of Tencent’s holdings.

Americans are unlikely to see new, foreign brands on grocery store shelves anytime soon. Instead, they will be buying Entenmann’s mini-chocolate chip cookies owned by Mexican firm Grupo Bimbo instead.

As a result of these trends, understanding the role of national culture for organizational behaviour may provide you with a competitive advantage in your career. In fact, sometime in your career, you may find yourself working as an expatriate. An expatriate is temporarily assigned to a position in a foreign country. Such an experience may be invaluable for your career and challenge you to increase your understanding and appreciation of differences across cultures.

How do cultures differ from each other? If you have ever visited a country different from your own, you probably have stories to tell about what aspects of the culture were different and which were similar. Maybe you have noticed that in many parts of Canada people routinely greet strangers with a smile when they step into an elevator or see them on the street, but the same behaviour of saying hello and smiling at strangers would be considered odd in many parts of Europe. In India and other parts of Asia, traffic flows with rules of its own, with people disobeying red lights, stopping and loading passengers in highways, or honking continuously for no apparent reason. In fact, when it comes to culture, we are like fish in the sea: we may not realize how culture is shaping our behaviour until we leave our own and go someplace else. Cultural differences may shape how people dress, act, eat, form relationships, address each other, and many other aspects of daily life.

Thinking about hundreds of different ways in which cultures may differ is not very practical when you are trying to understand how culture affects work behaviours. For this reason, the work of Geert Hofstede, a Dutch social scientist, is an important contribution to the literature. Hofstede studied IBM employees in 66 countries and showed variations among national cultures across four important dimensions. Research also shows that cultural variation with respect to these four dimensions influence employee job behaviours, attitudes, well-being, motivation, leadership, negotiations, and many other aspects of organizational behaviour (Hofstede, 1980; Tsui, Nifadkar, & Ou, 2007).

|

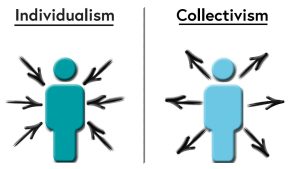

Individualism Cultures in which people define themselves as individuals and form looser ties with their groups. |

Collectivism Cultures where people have stronger bonds to their group and membership forms a person’s self-identity. |

|

|

|

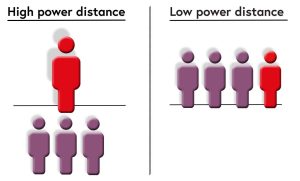

Low Power Distance A society that views an unequal distribution of power as relatively unacceptable. |

High Power Distance A society that views an unequal distribution of power as relatively acceptable. |

|

|

|

Low Uncertainty Avoidance Cultures in which people are comfortable in unpredictable situations and have high tolerance for ambiguity. |

High Uncertainty Avoidance Cultures in which people prefer predictable situations and have low tolerance for ambiguity. |

|

|

|

High orientation to achievement and success Cultures in which people value achievement and competitiveness, as well as acquisition of money and other material objects. |

Lower orientation to achievement and success Cultures in which people value maintaining good relationships, caring for the weak, and quality of life. |

|

|

Figure 2.3 Hofstede’s culture framework is a useful tool to understand the systematic differences across cultures. Source: Adapted from information in Geert Hofstede cultural dimensions. Retrieved November 12, 2008, from http://www.geert-hofstede.com/hofstede_dimen-sions.php.

Individualism-Collectivism

Individualistic cultures are cultures in which people define themselves as an individual and form loose ties with their groups. These cultures value autonomy and independence of the person, self-reliance, and creativity. Countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia are examples of individualistic cultures. In contrast, collectivistic cultures are cultures where people have stronger bonds to their groups and group membership forms a person’s self-identity. Asian countries such as China and Japan, as well as countries in South America are higher in collectivism.

In collectivistic cultures, people define themselves as part of a group. In fact, this may be one way to detect people’s individualism-collectivism level. When individualists are asked a question such as “Who are you? Tell me about yourself,” they are more likely to talk about their likes and dislikes, personal goals, or accomplishments. When collectivists are asked the same question, they are more likely to define themselves in relation to others, such as “I am Chinese” or “I am the daughter of a doctor and a homemaker. I have two brothers.” In other words, in collectivistic cultures, self-identity is shaped to a stronger extent by group memberships (Triandis, McCusker, & Hui, 1990).

Other traits of collectivist cultures are:

- Greater emphasis is placed on common goals than on individual pursuits.

- The rights of families and communities come before those of the individual.

- Group loyalty is encouraged.

- Decisions are based on what is best for the group.

- Compromise is favored when a decision needs to be made to achieve greater levels of peace.

Collectivists are more attached to their groups and have more permanent attachments to these groups. Conversely, individualists attempt to change groups more often and have weaker bonds to them. It is important to recognize that to collectivists the entire human universe is not considered to be their in- group. In other words, collectivists draw sharper distinctions between the groups they belong to and those they do not belong to. They may be nice and friendly to their in-group members while acting much more competitively and aggressively toward out-group members. This tendency has important work implications. While individualists may evaluate the performance of their colleagues more accurately, collectivists are more likely to be generous when evaluating their in-group members.

Freeborders, a software company based in San Francisco, California, found that even though it was against company policy, Chinese employees were routinely sharing salary information with their coworkers. This situation led them to change their pay system by standardizing pay at job levels and then giving raises after more frequent appraisals (Frauenheim, 2005; Hui & Triandis, 1986; Javidan & Dastmalchian, 2003; Gomez, Shapiro, & Kirkman, 2000).

Collectivistic societies emphasize conformity to the group. The Japanese saying “the nail that sticks up gets hammered down” illustrates that being different from the group is undesirable. In these cultures, disobeying or disagreeing with one’s group is difficult and people may find it hard to say no to their colleagues or friends. Instead of saying no, which would be interpreted as rebellion or at least be considered rude, they may use indirect ways of disagreeing, such as saying “I have to think about this” or “this would be difficult.” Such indirect communication prevents the other party from losing face but may cause misunderstandings in international communications with cultures that have a more direct style. Collectivist cultures may have a greater preference for team-based rewards as opposed to individual- based rewards.

Power Distance

Power distance refers to the degree to which the society views an unequal distribution of power as acceptable. Simply put, some cultures are more egalitarian than others.

Countries with high Power Distance scores are generally those with stark hierarchies, where the less powerful are taught to “know their place” and respect authority. High PDI scores correlate with deferential relationships between students and teachers, children and parents, wives and husbands, employees and employers, subjects and rulers.

Countries with low Power Distance scores, lack the observance of differences in rank and status. People from these countries are less likely to drastically change their manner of speaking depending on the status of the person they are addressing.

For example, Thailand is a high-power distance culture and starting from childhood, people learn to recognize who is superior, equal, or inferior to them. When passing people who are more powerful, individuals are expected to bow, and the more powerful the person, the deeper the bow would be (Pornpitakpan, 2000). Managers in high power distance cultures are treated with a higher degree of respect, which may surprise those in lower power distance cultures. A Citibank manager in Saudi Arabia was surprised when employees stood up every time he passed by (Denison, Haaland, & Goelzer, 2004). Similarly, in Turkey and India, students in elementary and high schools greet their teacher by standing up every time the teacher walks into the classroom. In these cultures, referring to a manager or a teacher with their first name would be extremely rude. The behaviours in high power distance cultures may easily cause misunderstandings with those from low power distance societies. For example, a limp handshake in India or a job candidate from Chad (North African country) who looks at the floor throughout the interview are in fact forms of showing respect, but these behaviours may be interpreted as a lack of confidence or even disrespect in low power distance cultures.

One of the most important ways in which power distance is manifested in the workplace is that in high power distance cultures, employees are unlikely to question the power and authority of their manager, and conformity to the manager will be expected. Managers in these cultures may be more used to an authoritarian style with lower levels of participative leadership demonstrated. People will be more sub- missive to their superiors and may take orders without questioning the manager (Kirkman, Gibson, & Shapiro, 2001). In these cultures, people may feel uncomfortable when they are asked to participate in decision making. For example, peers are much less likely to be involved in hiring decisions in high power distance cultures. Instead, these cultures seem to prefer paternalistic leaders—leaders who are authoritarian but make decisions while showing a high level of concern toward employees as if they were family members (Javidan & Dastmalchian, 2003; Ryan et al., 1999).

Uncertainty Avoidance

Uncertainty avoidance refers to the degree to which people feel threatened by ambiguous, risky, or unstructured situations. Cultures high in uncertainty avoidance prefer predictable situations and have low tolerance for ambiguity. Employees in these cultures expect a clear set of instructions and clarity in expectations. Therefore, there will be a greater level of creating procedures to deal with problems and writing out expected behaviours in manuals.

Cultures high in uncertainty avoidance prefer to avoid risky situations and attempt to reduce uncertainty. For example, one study showed that when hiring new employees, companies in high uncertainty avoidance cultures are likely to use a larger number of tests, conduct a larger number of interviews, and use a fixed list of interview questions (Ryan et al., 1999). Employment contracts tend to be more popular in cultures higher in uncertainty avoidance compared to cultures low in uncertainty avoidance (Raghuram, London, & Larsen, 2001). The level of change-oriented leadership seems to be lower in cultures higher in uncertainty avoidance (Ergeneli, Gohar, & Temirbekova, 2007). Companies operating in high uncertainty avoidance cultures also tend to avoid risky endeavors such as entering foreign target markets unless the target market is very large (Rothaermel, Kotha, & Steensma, 2006).

Germany is an example of a high uncertainty avoidance culture where people prefer structure in their lives and rely on rules and procedures to manage situations. Similarly, Greece is a culture relatively high in uncertainty avoidance, and Greek employees working in hierarchical and rule-oriented companies report lower levels of stress (Joiner, 2001). In contrast, cultures such as Iran and Russia are lower in uncertainty avoidance, and companies in these regions do not have rule-oriented cultures. When they create rules, they also selectively enforce rules and make a number of exceptions to them. In fact, rules may be viewed as constraining. Uncertainty avoidance may influence the type of organizations employees are attracted to. Japan’s uncertainty avoidance is associated with valuing job security, while in uncertainty-avoidant Latin American cultures, many job candidates prefer the stability of bigger and well-known companies with established career paths.

Orientation to Achievement and Success (previously called Masculinity–Femininity)

Masculine cultures value achievement, competitiveness, and acquisition of money and other material objects. Japan and Hungary are examples of masculine cultures. Masculine cultures are also characterized by a separation of gender roles. In these cultures, men are more likely to be assertive and competitive compared to women.

In contrast, feminine cultures are cultures that value maintaining good relationships, caring for the weak, and emphasizing quality of life. In these cultures, values are not separated by gender, and both women and men share the values of maintaining good relationships. Sweden and the Netherlands are examples of feminine cultures.

The level of masculinity inherent in the culture has implications for the behaviour of individuals as well as organizations. For example, in masculine cultures, the ratio of CEO pay to other management-level employees tends to be higher, indicating that these cultures are more likely to reward CEOs with higher levels of pay as opposed to other types of rewards (Tosi & Greckhamer, 2004). The femininity of a culture affects many work practices, such as the level of work/life balance. In cultures high in femininity such as Norway and Sweden, work arrangements such as telecommuting seem to be more popular compared to cultures higher in masculinity like Italy and the United Kingdom.

Key Takeaways

With the increasing prevalence of international business as well as diversification of the domestic workforce in many countries, understanding how culture affects organisational behaviour is becoming important. Individualism-collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity-femininity are four key dimensions in which cultures vary. The position of a culture on these dimensions affects the suitable type of management style, reward systems, employee selection, and ways of motivating employees.

Exercises

- What is culture? Do countries have uniform national cultures?

- How would you describe your own home country’s values on the four dimensions of culture?

- Reflect on a time when you experienced a different culture or interacted with someone from a different culture. How did the cultural differences influence your interaction?

- How does culture influence the proper leadership style and reward system that would be suitable in an organisation?

Managing Diversity for Success: The Case of IBM

When you are a company that operates in over 170 countries with a workforce of over 398,000 employees, understanding and managing diversity effectively is not optional—it is a key business priority. A company that employs individuals and sells products worldwide needs to understand the diverse groups of people that make up the world.

Starting from its early history in the United States, IBM Corporation (NYSE: IBM) has been a pioneer in valuing and appreciating its diverse workforce. In 1935, almost 30 years before the Equal Pay Act guaranteed pay equality between the sexes, then IBM president Thomas Watson promised women equal pay for equal work. In 1943, the company had its first female vice president. Again, 30 years before the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) granted women unpaid leave for the birth of a child, IBM offered the same benefit to female employees, extending it to one year in the 1960s and to three years in 1988. In fact, the company ranks in the top 100 on Working Mother magazine’s “100 Best Companies” list and has been on the list every year since its inception in 1986. It was awarded the honour of number 1 for multicultural working women by the same magazine in 2009.

IBM has always been a leader in diversity management. Yet, the way diversity was managed was primarily to ignore differences and provide equal employment opportunities. This changed when Louis Gerstner became CEO in 1993.

Gerstner was surprised at the low level of diversity in the senior ranks of the company. For all the effort being made to promote diversity, the company still had what he perceived a masculine culture.

In 1995, he created eight diversity task forces around demographic groups such as women and men, as well as Asians, African Americans, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) individuals, Hispanics, Native Americans, and employees with disabilities. These task forces consisted of senior-level, well-respected executives and higher-level managers, and members were charged with gaining an understanding of how to make each constituency feel more welcome and at home at IBM. Each task force conducted a series of meetings and surveyed thousands of employees to arrive at the key factors concerning each particular group. For example, the presence of a male-dominated culture, lack of networking opportunities, and work-life management challenges topped the list of concerns for women. Asian employees were most concerned about stereotyping, lack of networking, and limited employment development plans. African American employee concerns included retention, lack of networking, and limited training opportunities. Armed with a list of priorities, the company launched a number of key programs and initiatives to address these issues. As an example, employees looking for a mentor could use the company’s website to locate one willing to provide guidance and advice. What is probably most unique about this approach is that the company acted on each concern whether it was based on reality or perception. They realized that some women were concerned that they would have to give up leading a balanced life if they wanted to be promoted to higher management, whereas 70% of the women in higher levels actually had children, indicating that perceptual barriers can also act as a barrier to employee aspirations. IBM management chose to deal with this particular issue by communicating better with employees as well as through enhancing their networking program.

The company excels in its recruiting efforts to increase the diversity of its pool of candidates. One of the biggest hurdles facing diversity at IBM is the limited minority representation in fields such as computer sciences and engineering. For example, only 4% of students graduating with a degree in computer sciences are Hispanic. To tackle this issue, IBM partners with colleges to increase recruitment of Hispanics to these programs. In a program named EXITE (Exploring Interest in Technology and Engineering), they bring middle school female students together for a week-long program where they learn math and science in a fun atmosphere from IBM’s female engineers. To date, over 3,000 girls have gone through this program.

What was the result of all these programs? IBM tracks results through global surveys around the world and identifies which programs have been successful and which issues are no longer viewed as problems. These programs were instrumental in more than tripling the number of female executives worldwide as well as doubling the number of minority executives. The number of LBGT executives increased sevenfold, and executives with disabilities tripled. With growing emerging markets and women and minorities representing a $1.3 trillion market, IBM’s culture of respecting and appreciating diversity is likely to be a source of competitive advantage.

Based on information from Ferris, M. (2004, Fall). What everyone said couldn’t be done: Create a global women’s strategy for IBM. The Diversity Factor, 12(4), 37–42; IBM hosts second annual Hispanic education day. (2007, December–January). Hispanic Engineer, 21(2), 11; Lee, A. M. D. (2008, March). The power of many: Diversity’s competitive advantage. Incentive, 182(3), 16–21; Thomas, D. A. (2004, September). Diver- sity as strategy. Harvard Business Review, 82(9), 98–108.

Exercises

- IBM has been championed for its early implementation of equality among its workforce. At the time, many of these policies seemed radical. To IBM’s credit, the movement toward equality worked out exceptionally well for them. Have you experienced policy changes that might seem radical? Have these policies worked out? What policies do you feel are still lacking in the workforce?

- If you or your spouse is currently employed, how difficult would it be to take time off for having a child?

- Some individuals feel that so much focus is put on making the workplace better for under-represented groups that the majority of the workforce becomes neglected. Do you feel this was the case at IBM? Why or why not? How can a company ensure that no employee is neglected, regardless of demographic group?

- What types of competitive advantages could IBM have gained from having such a diverse workforce?

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this chapter we reviewed the implications of demographic and cultural diversity for organizational behaviour. Management of diversity effectively promises a number of benefits for companies and may be a competitive advantage. Yet, challenges such as natural human tendencies to associate with those similar to us and using stereotypes in decision making often act as barriers to achieving this goal. By creating a work environment where people of all origins and traits feel welcome, organizations will make it possible for all employees to feel engaged with their work and remain productive members of the organization.

2.5 Exercises

Ethical Dilemma

You are working for the police department of your city. When hiring employees, the department uses a physical ability test in which candidates are asked to do 30 push-ups and 25 sit-ups, as well as climb over a 4-foot wall. When candidates take this test, it seems that about 80% of the men who take the test actually pass it, while only 10% of the female candidates pass the test. Do you believe that this is a fair test? Why or why not? If you are asked to review the employee selection procedures, would you make any changes to this system? Why or why not?

Individual Exercise

A colleague of yours is being sent to India as a manager for a call center. She just told you that she feels very strongly about the following issues:

- Democratic leaders are the best leaders because they create a more satisfied workforce.

- Employees respond best to individual-based pay incentives and bonuses as tools for motivation.

- Employees should receive peer feedback about their performance level SO that they can get a better sense of how well they are performing.

After doing some research on the business environment and national culture in India, how would you advise your colleague to behave? Should she try to transfer these three managerial practices to the Indian context? Why or why not?

Group Exercise: Diversity Dilemmas

Imagine that you are working in the HR department of your company. You come across the following scenarios in which your input has been sought. Discuss each scenario and propose an action plan for management.

- Aimee is the mother of a newborn. She is very dedicated to her work but she used to stay for longer hours at work before she had her baby. Now she tries to schedule her work SO that she leaves around 5:00 p.m. Her immediate manager feels that Aimee is no longer dedicated or com- mitted to her work and is considering passing her over for a promotion. Is this decision fair?

- Jack is a married male, while John is single. Your company has an assignment in a branch in Mexico that would last a couple of years. Management feels that John would be better for this assignment because he is single and is free to move. Is this decision fair?

- A manager receives a request from an employee to take off a Wednesday for religious reasons. The manager did not know that this employee was particularly religious and does not believe that the leave is for religious reasons. The manager believes that the employee is going to use this day as a personal day off. Should the manager investigate the situation?

- A sales employee has painful migraines intermittently during the work day. She would like to take short naps during the day as a preventative measure and she also needs a place where she can nap when a migraine occurs. Her immediate manager feels that this is unfair to the rest of the employees.

- A department is looking for an entry-level cashier. One of the job applicants is a cashier with 30 years of experience. The department manager feels that this candidate is overqualified for the job and is likely to be bored and leave the job in a short time.

Instead, they want to pursue a candidate with 6 months of work experience who seems like a better fit for the position.

Mini Case Scenario

Deriving benefits of Diversity & Inclusion needs to be managed

Hector Resources Inc. is a mining company operating in a remote area of Canada. The company had hired a significant number of Indigenous workers from the nearby communities to work in the mine. However, they were facing several challenges in managing the workforce due to cultural differences.

One of the primary challenges was the communication barrier. The Indigenous workers spoke their local language, which was different from the language spoken by the non-Indigenous supervisors. This led to misunderstandings, and sometimes the workers were not able to understand the instructions given to them. This resulted in a loss of productivity and increased safety risks.

Another challenge was the difference in work values and expectations. The Indigenous workers had different attitudes towards time management, work ethic, and hierarchy. For example, they placed a high value on family and community obligations and were more likely to prioritize them over work. This led to conflicts with the non-Indigenous supervisors, who expected the workers to prioritize work over other obligations.

Adam Maxwell, the CEO at Hector Resources Inc. had recently attended a seminar on the benefits of adopting Diversity and Inclusion practices by firms and was determined to see that his company gained from these. However, he realized that managing an Indigenous workforce requires a deep understanding of their culture, values, and traditions. Organizations must be willing to adapt their management practices to accommodate these differences and create a work environment that is inclusive and respectful of cultural diversity. By doing so, organizations can benefit from the unique perspectives and skills of Indigenous workers and create a more harmonious and productive workplace.

A concerted effort was required if the company wanted to avail of the benefits.

Adam Maxwell wants to hire you as an external consultant to propose measures to address the challenges such as barriers and differences identified above. If your proposal is seen to aid with the Diversity and Inclusion efforts, you would be hired to implement your proposal.

Propose specific measures that the company should undertake to tackle the identified challenges.