8.1 Understanding Communication

Communication is vital to organizations—it’s how we coordinate actions and achieve goals. It is defined in Webster’s dictionary as a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behaviours. We know that 50% to 90% of a manager’s time is spent communicating (Schnake et al., 1990), and communication ability is related to a manager’s performance (Penley et al., 1991). In most work environments, a miscommunication is an annoyance—it can interrupt workflow by causing delays and interpersonal strife. But, in some work arenas, like operating rooms and airplane cockpits, communication can be a matter of life and death.

So, just how prevalent is miscommunication in the workplace? You may not be surprised to learn that the relationship between miscommunication and negative outcomes is very strong. Data suggest that deficient interpersonal communication was a causal factor in approximately 70% to 80% of all accidents over the last 20 years.

Poor communication can also lead to lawsuits. For example, you might think that malpractice suits are filed against doctors based on the outcome of their treatments alone. But a 1997 study of malpractice suits found that a primary influence on whether or not a doctor is sued is the doctor’s communication style. While the combination of a bad outcome and patient unhappiness can quickly lead to litigation, a warm, personal communication style leads to greater patient satisfaction. Simply put, satisfied patients are less likely to sue.

In business, poor communication costs money and wastes time. One study found that 14% of each workweek is wasted on poor communication (Armour, 1998). In contrast, effective communication is an asset for organizations and individuals alike. Effective communication skills, for example, are an asset for job seekers. A recent study of recruiters at 85 business schools ranked communication and interpersonal skills as the highest skills they were looking for, with 89% of the recruiters saying they were important (Alsop, 2006). On the flip side, good communication can help a company retain its star employees. Surveys find that when employees think their organizations do a good job of keeping them informed about matters that affect them and when they have access to the information they need to do their jobs, they are more satisfied with their employers. So can good communication increase a company’s market value? The answer seems to be yes. “When you foster ongoing communications internally, you will have more satisfied employees who will be better equipped to communicate with your customers effectively,” says Susan Meisinger, president and CEO of the Society for Human Resource Management. Research finds that organizations that can improve their communication integrity also increase their market value by as much as 7% (Meisinger, 2003). We will explore the definition and benefits of effective communication in our next section.

The Communication Process

Communication fulfills three main functions within an organization, including coordination, the transmission of information, and sharing of emotions and feelings. All these functions are vital to a successful organization. The coordination of effort within an organization helps people work toward the same goals. Transmitting information is a vital part of this process. Sharing emotions and feelings bonds teams and unites people in times of celebration and crisis. Effective communication helps people grasp issues, build rapport with coworkers, and achieve consensus. So, how can we communicate effectively? The first step is to understand the communication process.

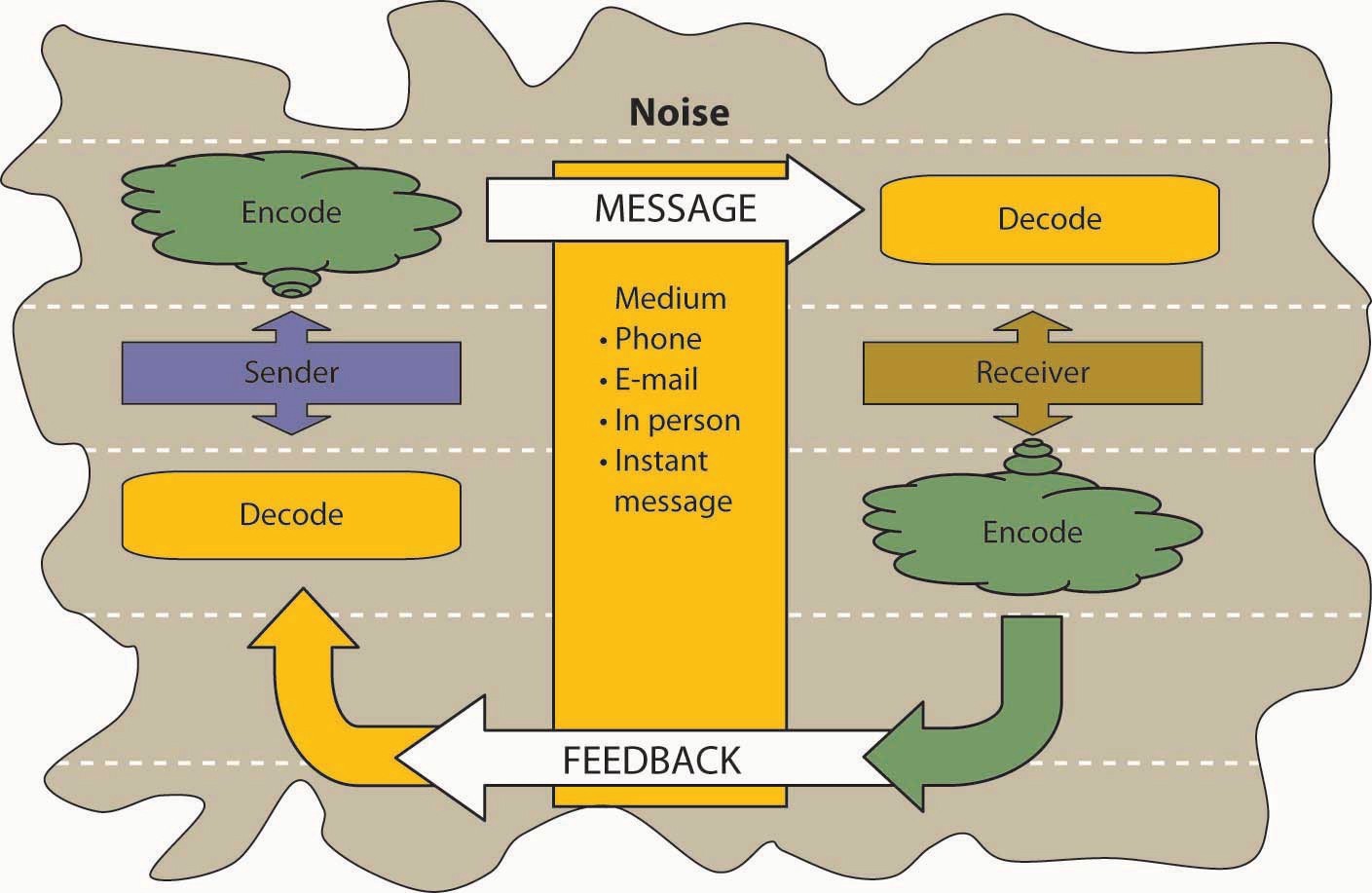

We all exchange information with others countless times each day by phone, e-mail, the printed word, and of course, in person. Let us take a moment to see how a typical communication cycle works using this as a guide.

A sender, such as a boss, coworker, or customer, originates the message with a thought. For example, the boss’s thought could be: “Get more printer toner cartridges!”

The sender encodes the message, translating the idea into words.

The boss may communicate this thought by saying, “Hey you guys, let’s order more printer toner cartridges.”

The medium of this encoded message may be spoken words, written words, or signs. The receiver is the person who receives the message.

The receiver decodes the message by assigning meaning to the words.

In this example, our receiver, Bill, has a to-do list a mile long. “The boss must know how much work I already have,” the receiver thinks. Bill’s mind translates his boss’s message as, “Could you order some printer toner cartridges, in addition to everything else I asked you to do this week…if you can find the time?”

The meaning that the receiver assigns may not be the meaning that the sender intended because of factors such as noise. Noise is anything that interferes with or distorts the message being transformed. Noise can be external in the environment (such as distractions), or it can be within the receiver. For example, the receiver may be extremely nervous and unable to pay attention to the message. Noise can even occur within the sender: The sender may be unwilling to take the time to convey an accurate message, or the words that are chosen can be ambiguous and prone to misinterpretation.

Picture the next scene. The place: a staff meeting. The time: a few days later. Bill’s boss believes the message about printer toner has been received.

“Are the printer toner cartridges here yet?” Bill’s boss asks.

“You never said it was a rush job!” Bill protests.

“But!”

“But!”

Miscommunications like these happen in the workplace every day. We’ve seen that miscommunication does occur in the workplace, but how does miscommunication happen? It helps to think of the communication process. The series of arrows pointing the way from the sender to the receiver and back again can, and often do, fall short of their target.

Key Takeaways

Communication is vital to organisations. Poor communication is prevalent between senders and receivers. Communication fulfills three functions within organisations, including coordination, the transmission of information, and sharing emotions and feelings. Noise can disrupt or distort communication.

Exercises

- Where have you seen the communication process break down at work? At school? At home?

- Explain how miscommunication might be related to an accident at work?

- Give an example of noise during the communication process.

Communication Barriers

Barriers to Effective Communication

The biggest single problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

– George Bernard Shaw

Filtering

Filtering is the distortion or withholding of information to manage a person’s reactions. Some examples of filtering include a manager keeping a division’s negative sales figures from a superior, in this case, the vice president. The old saying, “Don’t shoot the messenger!” illustrates the tendency of receivers to vent their negative response to unwanted messages to the sender. A gatekeeper (the vice president’s assistant, perhaps) who doesn’t pass along a complete message is also filtering. Additionally, the vice president may delete the e-mail announcing the quarter’s sales figures before reading it, blocking the message before it arrives.

As you can see, filtering prevents members of an organization from getting the complete picture of a situation. To maximize your chances of sending and receiving effective communications, it’s helpful to deliver a message in multiple ways and to seek information from multiple sources. In this way, the impact of any one person’s filtering will be diminished.

Since people tend to filter bad news more during upward communication, it is also helpful to remember that those below you in an organization may be wary of sharing bad news. One way to defuse this tendency to filter is to reward employees who convey information upward, regardless of whether the news is good or bad.

Here are some of the criteria that individuals may use when deciding whether to filter a message or pass it on:

- Past experience: Were previous senders rewarded for passing along news of this kind in the past, or were they criticized?

- Knowledge and perception of the speaker: Has the receiver’s direct superior made it clear that “no news is good news?”

- Emotional state, involvement with the topic, and level of attention: Does the sender’s fear of failure or criticism prevent the message from being conveyed? Is the topic within the sender’s realm of expertise, increasing confidence in the ability to decode the message, or is the sender out of a personal comfort zone when it comes to evaluating the message’s significance? Are personal concerns impacting the sender’s ability to judge the message’s value?

Once again, filtering can lead to miscommunications in business. Listeners translate messages into their own words, each creating a unique version of what was said (Alessandra, 1993).

Selective Perception

Small things can command our attention when we’re visiting a new place—a new city or a new company. Over time, however, we begin to make assumptions about the environment based on our past experiences. Selective perception refers to filtering what we see and hear to suit our own needs. This process is often unconscious. We are bombarded with too much stimuli every day to pay equal attention to everything, so we pick and choose according to our own needs. Selective perception is a time-saver and a necessary tool in a complex culture. But it can also lead to mistakes.

Think back to the example conversation between the person asked to order more toner cartridges and his boss earlier in this chapter. Since Bill found the to-do list from his boss to be unreasonably demanding, he assumed the request could wait. (How else could he do everything else on the list?) The boss, assuming that Bill had heard the urgency of her request, assumed that Bill would place the order before returning to previously stated tasks. Both members of this organization were using selective perception to evaluate the communication. Bill’s perception was that the task could wait. The boss’s perception was that a timeframe was clear, though unstated. When two selective perceptions collide, a misunderstanding occurs.

Information Overload

Messages reach us in countless ways every day. Some messages are societal—advertisements that we may hear or see in the course of our day. Others are professional—e-mails, memos, and voice mails, as well as conversations with our colleagues. Others are personal—messages from and conversations with our loved ones and friends.

Add these together, and it’s easy to see how we may be receiving more information than we can take in.

This state of imbalance is known as information overload, which occurs “when the information processing demands on an individual’s time to perform interactions and internal calculations exceed the supply or capacity of time available for such processing” (Schick, Gordon, & Haka, 1990). Others note that information overload is “a symptom of the high-tech age, which is too much information for one human being to absorb in an expanding world of people and technology. It comes from all sources, including TV, newspapers, and magazines as well as wanted and unwanted regular mail, e-mail, and faxes. It has been exacerbated enormously because of the formidable number of results obtained from Web search engines.” Other research shows that working in such a fragmented fashion significantly impacts efficiency, creativity, and mental acuity (Overholt, 2001).

Going back to our example of Bill, let’s say he’s in his office on the phone with a supplier. While he’s talking, he hears the chime of his e-mail alerting him to an important message from his boss. He’s scanning through it quickly while still on the phone when a coworker pokes her head into his office, saying Bill’s late for a staff meeting. The supplier on the other end of the phone line has just given him a choice among the products and delivery dates he requested. Bill realizes he missed hearing the first two options, but he doesn’t have time to ask the supplier to repeat them all or to try reconnecting with him at a later time. He chooses the third option—at least he heard that one, he reasons, and it seemed fair. How good was Bill’s decision amidst all the information he was processing at the same time?

Workplace Gossip

The informal gossip network known as the grapevine is a lifeline for many employees seeking information about their company (Kurland & Pelled, 2000). Researchers agree that the grapevine is an inevitable part of organizational life. Research finds that 70% of all organizational communication occurs at the grapevine level (Crampton, 1998). Employees trust their peers as a source of information, but the grapevine’s informal structure can be a barrier to effective communication from the managerial point of view. Its grassroots structure gives it greater credibility in the minds of employees than information delivered through official channels, even when that information is false. Some downsides of the office grapevine are that gossip offers politically minded insiders a powerful tool for disseminating communication (and self-promoting miscommunications) within an organization. In addition, the grapevine lacks a specific sender, which can create a sense of distrust among employees: Who is at the root of the gossip network? When the news is volatile, suspicions may arise as to the person or person behind the message. Managers who understand the grapevine’s power can use it to send and receive messages of their own. They can also decrease the grapevine’s power by sending official messages quickly and accurately should big news arise.

Gender Differences in Communication

Men and women work together every day, but their different styles of communication can sometimes work against them. Generally speaking, women like to ask questions before starting a project, while men tend to “jump right in.” A male manager who’s unaware of how most women communicate their readiness to work may misperceive a ready employee as not being prepared.

Another difference that has been noticed is that men often speak in sports metaphors, while many women use their home as a starting place for analogies. Women who believe men are “only talking about the game” may be missing out on a chance to participate in a division’s strategy and opportunities for teamwork and “rallying the troops” for success (Krotz).

“It is important to promote the best possible communication between men and women in the workplace,” notes gender policy advisor Dee Norton, who provided the above example. “As we move between the male and female cultures, we sometimes have to change how we behave (speak the language of the other gender) to gain the best results from the situation. Successful organizations of the future are going to have leaders and team members who understand, respect, and apply the rules of gender culture appropriately” (CDR Dee Norton, 2008).

As we have seen, differences in men’s and women’s communication styles can lead to misunderstandings in the workplace. Being aware of these differences, however, can be the first step in learning to work with them instead of around them. Keep in mind that men tend to focus more on competition, data, and orders in their communications, while women tend to focus more on cooperation, intuition, and requests. Both styles can be effective in the right situations, but understanding the differences is the first step in avoiding misunderstandings.

Poor Listening

The greatest compliment that was ever paid to me was when one asked me what I thought and attended to my answer.

– Henry David Thoreau

A sender may strive to deliver a message. But the receiver’s ability to listen effectively is equally vital to successful communication. The average worker spends 55% of their workdays listening. Managers listen up to 70% of each day. Unfortunately, listening doesn’t lead to understanding in every case.

From several different perspectives, listening matters. Former Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca lamented, “I only wish I could find an institute that teaches people how to listen. After all, a good manager needs to listen at least as much as he needs to talk” (Iacocca & Novak, 1984). Research shows that listening skills were related to promotions (Sypher, Bostrom, & Seibert, 1989).

Listening matters. Listening takes practice, skill, and concentration. Alan Gulick, a Starbucks Corporation spokesperson, believes better listening can improve profits. If every Starbucks employee misheard one $10 order each day, their errors would cost the company a billion dollars annually. To teach its employees to listen, Starbucks created a code that helps employees taking orders hear the size, flavor, and use of milk or decaffeinated coffee. The person making the drink echoes the order aloud.

How Can You Improve Your Listening Skills?

Cicero said, “Silence is one of the great arts of conversation.” How often have we been in a conversation with someone else when we are not listening but itching to convey our portion? This behaviour is known as “rehearsing.” It suggests the receiver has no intention of considering the sender’s message and is preparing to respond to an earlier point instead. Effective communication relies on another kind of listening: active listening.

Active listening can be defined as giving full attention to what other people are saying, taking time to understand the points being made, asking questions as needed, and not interrupting at inappropriate times (O*NET Resource Center). Active listening creates a real-time relationship between the sender and receiver by acknowledging the content and receipt of a message. As we’ve seen in the Starbucks example above, repeating and confirming a message’s content offers a way to confirm that the correct content is flowing between colleagues. The process creates a bond between coworkers while increasing the flow and accuracy of messaging.

Becoming a More Effective Listener

As we’ve seen above, active listening creates a more dynamic relationship between a receiver and a sender. It strengthens personal investment in the information being shared. It also forges healthy working relationships among colleagues by making speakers and listeners equally valued members of the communication process.

Many companies offer public speaking courses for their staff, but what about “public listening”? Here are some more ways you can build your listening skills by becoming a more effective listener and banishing communication freezers from your discussions.

- Start by stopping. Take a moment to inhale and exhale quietly before you begin to listen. Your job as a listener is to receive information openly and accurately.

- Don’t worry about what you’ll say when the time comes. Silence can be a beautiful thing.

- Join the sender’s team. When the sender pauses, summarize what you believe has been said. “What I’m hearing is that we need to focus on marketing as well as sales. Is that correct?” Be attentive to physical as well as verbal communications. “I hear you saying that we should focus on marketing, but the way you’re shaking your head tells me the idea may not really appeal to you—is that right?”

- Don’t multitask while listening. Listening is a full-time job. It’s tempting to multitask when you and the sender are in different places, but doing that is counterproductive. The human mind can only focus on one thing at a time. Listening with only part of your brain increases the chances that you’ll have questions later, ultimately requiring more of the speaker’s time. (And when the speaker is in the same room, multitasking signals a disinterest that is considered rude.)

- Try to empathize with the sender’s point of view. You don’t have to agree, but can you find common ground (Barrett, 2006; Ten tips: Active listening, 2007)?

Communication Freezers

Communication freezers put an end to effective communication by making the receiver feel judged or defensive. Typical communication stoppers include criticizing, blaming, ordering, judging, or shaming the other person. Some examples of things to avoid saying include the following:

1. Telling the other person what to do:

- “You must…”

- “You cannot…”

2. Threatening with “or else” implied:

- “You had better…”

- “If you don’t…”

3. Making suggestions or telling the other person what they ought to do:

- “You should…”

- “It’s your responsibility to…”

4. Attempting to educate the other person:

- “Let me give you the facts.”

- “Experience tells us that…”

5. Judging the other person negatively:

- “You’re not thinking straight.”

- “You’re wrong.”

6. Giving insincere praise:

- “You have so much potential.”

- “I know you can do better than this.”

7. Psychoanalyzing the other person:

- “You’re jealous.”

- “You have problems with authority.”

8. Making light of the other person’s problems by generalizing:

- “Things will get better.”

- “Behind every cloud is a silver lining.”

9. Asking excessive or inappropriate questions (Tramel & Reynolds, 1981; Communication stoppers).