9.1 Introduction

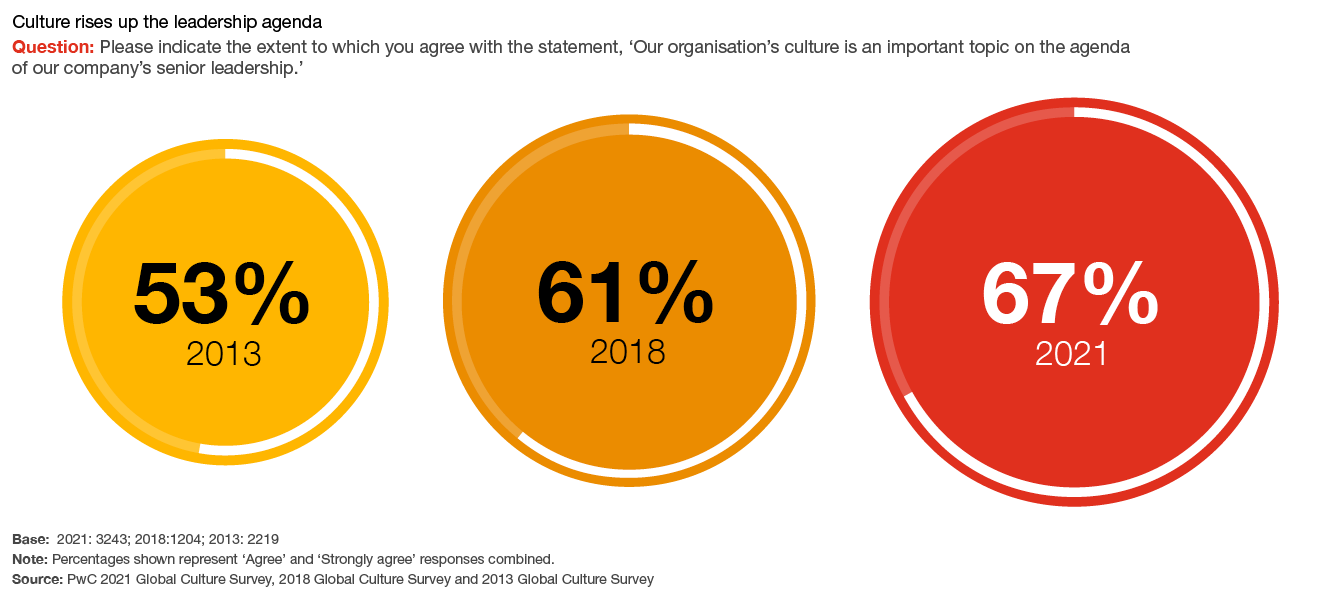

In a 2021 Global Culture Survey of 3,200 leaders and employees worldwide, PricewaterhouseCoopers, a leading, global consulting company highlighted the following findings:

- 67% of survey respondents said culture is more important than strategy or operations.

Just like individuals, you can think of organizations as having their own personalities, more typically known as organizational cultures. Understanding how culture is created, communicated, and changed will help you be more effective in your organizational life. But first, let’s define organizational culture.

Understanding Organizational Culture

What Is Organizational Culture?

Organizational culture refers to a system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that show employees what is appropriate and inappropriate behaviour (Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003; Kerr & Slocum Jr., 2005). These values have a strong influence on employee behaviour as well as organizational performance. In fact, the term organizational culture was made popular in the 1980s when Peters and Waterman’s best-selling book In Search of Excellence made the argument that company success could be attributed to an organizational culture that was decisive, customer oriented, empowering, and people oriented. Since then, organizational culture has become the subject of numerous research studies, books, and articles. However, organizational culture is still a relatively new concept. In contrast to a topic such as leadership, which has a history spanning several centuries, organizational culture is a young but fast-growing area within organizational behaviour.

Culture is by and large invisible to individuals. Even though it affects all employee behaviours, thinking, and behavioural patterns, individuals tend to become more aware of their organization’s culture when they have the opportunity to compare it to other organizations. If you have worked in multiple organizations, you can attest to this. Maybe the first organization you worked at was a place where employees dressed formally. It was completely inappropriate to question your boss in a meeting; such behaviours would only be acceptable in private. It was important to check your e-mail at night as well as during weekends or else you would face questions on Monday about where you were and whether you were sick. Contrast this company to a second organization where employees dress more casually. You are encouraged to raise issues and question to your boss or peers, even in front of clients. What is more important is not to maintain impressions but to arrive at the best solution to any problem. It is widely known that family life is very important, so it is acceptable to leave work a bit early to go to a family event. Additionally, you are not expected to do work at night or over the weekends unless there is a deadline. These two hypothetical organizations illustrate that organizations have different cultures, and culture dictates what is right and what is acceptable behaviour as well as what is wrong and unacceptable.

Why Does Organizational Culture Matter?

Some key questions you will ask yourself as you embark upon and over your career are:

“What should I do to get ahead in my organization? What makes people successful here? What will make me successful?”

Charles O’Reilly, co-director of the Stanford Graduate School of Business, posed that question and invited VMware’s (an American cloud computing) employees to reflect on what the company rewarded.

Employees started filling the board with the usual suspects—innovate, work hard, be open, and be collaborative. But with prompting, more specific behaviors started to appear: “Be available on email 24×7,” “Sound smart,” and “Get consensus on your decisions.” Once the team had finished, Professor O’Reilly pointed at the whiteboard and said, “That’s your culture. Your culture is the behaviors you reward and punish.”

The discussion about the behaviors that are rewarded and punished is much harder than it seems and leaders often struggle with this exercise. Listing values is easy; connecting them to actual behaviors is a different story.

Research indicates that stated values often don’t have a significant impact and can even have a negative effect. An MIT Sloan study found no correlation between a company’s expressed values and how employees felt they lived up to them. For example, promoting diversity but not supporting it with action can do more harm than good. Statements such as “We don’t discriminate” create an impression that the organization has achieved equity and fairness when, in fact, it hasn’t.

Behavioral cues, on the other hand, provide concrete guidance on how to translate values into actions. Leaders must clarify why they matter. According to the same study by MIT, less than one-quarter of companies connect values with behaviors, and a significant majority fail to link beliefs with business success.

You can’t call your culture “transparent” if people are afraid of speaking truth to power. You can’t say you have a “collaborative” workplace if you regularly promote selfish employees. You can’t pronounce your culture “innovative” if breakthrough ideas are often killed before they see the light of day.

An organization’s culture may be one of its strongest assets, as well as its biggest liability. In fact, it has been argued that organizations that have a rare and hard-to-imitate organizational culture benefit from it as a competitive advantage (Barney, 1986). In a survey conducted by the management consulting firm Bain & Company in 2007, worldwide business leaders identified corporate culture as important as corporate strategy for business success (Why culture can mean life or death, 2007). This comes as no surprise to many leaders of successful businesses, who are quick to attribute their company’s success to their organization’s culture.

Culture, or shared values within the organization, may be related to increased performance. Researchers found a relationship between organizational cultures and company performance, with respect to success indicators such as revenues, sales volume, market share, and stock prices (Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Marcoulides & Heck, 1993). At the same time, it is important to have a culture that fits with the demands of the company’s environment. To the extent shared values are proper for the company in question, company performance may benefit from culture (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987). For example, if a company is in the high-tech industry, having a culture that encourages innovativeness and adaptability will support its performance. However, if a company in the same industry has a culture characterized by stability, a high respect for tradition, and a strong preference for upholding rules and procedures, the company may suffer as a result of its culture. In other words, just as having the “right” culture may be a competitive advantage for an organization, having the “wrong” culture may lead to performance difficulties, may be responsible for organizational failure, and may act as a barrier preventing the company from changing and taking risks.

In addition to having implications for organizational performance, organizational culture can dictate employee behaviour. Culture is in fact a more powerful way of controlling and managing employee behaviours than organizational rules and regulations. When problems are unique, rules tend to be less helpful. Instead, creating a culture of customer service achieves the same result by encouraging employees to think like customers, knowing that the company priorities in this case are clear: keeping the customer happy is preferable to other concerns such as saving the cost of a refund.

Levels of Organizational Culture

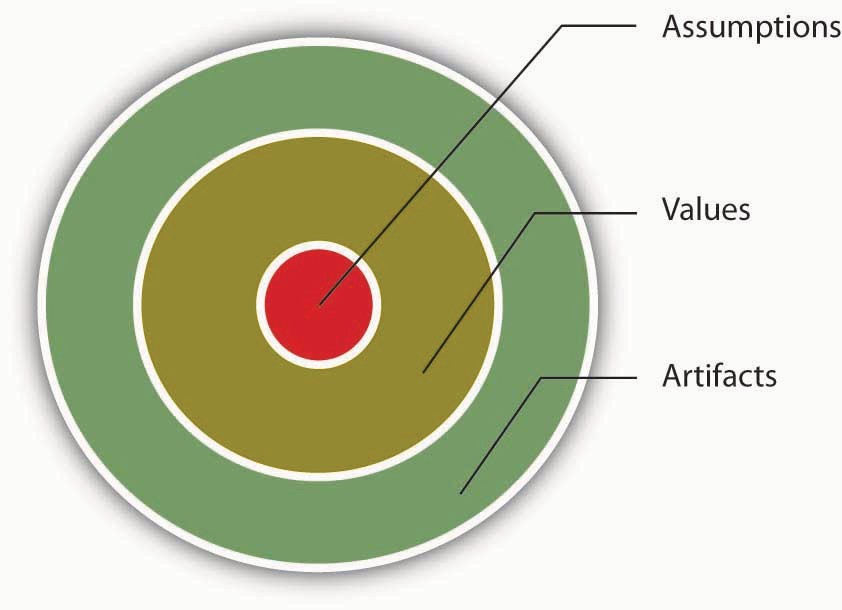

Organizational culture consists of some aspects that are relatively more visible, as well as aspects that may lie below one’s conscious awareness. Organizational culture can be thought of as consisting of three interrelated levels (Schein, 1992).

At the deepest level, below our awareness lie basic assumptions. Assumptions are taken for granted, and they reflect beliefs about human nature and reality. Organizational assumptions are usually “known,” but are not discussed, nor are they written or easily found. They are comprised of unconscious thoughts, beliefs, perceptions, and feelings (Schein, 2004).

“This will be difficult!”

In some cultures, like the US, this can mean “Yes, we can do that!”

In others, like Japan, this can mean, “No, it’s not possible.”

These are examples of cultural assumptions that often creep into our daily lives.

At the second level, values exist. Values are shared principles, standards, and goals. Values are officially introduced in a company’s mission, vision, and values statements.

HubSpot (an American developer and marketer of software products) has about 73,400 customers and more than 3,800 employees in the company as at February 2022 and have more than $674 million in annual revenue. HubSpot culture is driven by a shared passion for our mission and metrics. It is a culture of amazing, growth-minded people whose values include using good judgment and solving for the customer. Employees who work at HubSpot have HEART: Humble, Empathetic, Adaptable, Remarkable, Transparent. These are HubSpot’s key values.

Finally, at the surface we have artifacts, or visible, tangible aspects of organizational culture. For example, in an organization, one of the basic assumptions employees and managers share might be that happy employees benefit their organizations. This assumption could translate into values such as social equality, high quality relationships, and having fun. The artifacts reflecting such values might be an executive “open door” policy, an office layout that includes open spaces and gathering areas equipped with pool tables, and frequent company picnics in the workplace. For example, Alcoa Inc. designed their headquarters to reflect the values of making people more visible and accessible, and to promote collaboration (Stegmeier, 2008). In other words, understanding the organization’s culture may start from observing its artifacts: the physical environment, employee interactions, company policies, reward systems, and other observable characteristics.

When you are interviewing for a position, observing the physical environment, how people dress, where they relax, and how they talk to others is definitely a good start to understanding the company’s culture. However, simply looking at these tangible aspects is unlikely to give a full picture of the organization. An important chunk of what makes up culture exists below one’s degree of awareness. The values and, at a deeper level, the assumptions that shape the organization’s culture can be uncovered by observing how employees interact and the choices they make, as well as by inquiring about their beliefs and perceptions regarding what is right and appropriate behaviour.

These are examples of how leading brands link values to behaviours and thereby enable a productive, performance driven, culture:

Amazon punishes “complacency” and having a “Day 2 mentality.” Mediocrity is not welcomed. The tech giant rewards speed, relentlessness, and intellectual autonomy. This is consistent with Amazon’s aggressive culture.

HubSpot punishes taking shortcuts to achieve short-term results. Conversely, it rewards simplicity, being a “culture-add” (someone who actively improves the company), work and life balance, and results delivered, not hours worked.

Slack (an instant messaging program) punishes “brilliant jerks.” There’s no room for people who are disrespectful or not team players. Instead, Slack rewards empathy, a characteristic that’s crucial to getting a job at the tech company.

Key Takeaways

Organisational culture is a system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that help individuals within an organisation understand which behaviours are and are not appropriate within an organisation. Cultures can be a source of competitive advantage for organisations. Strong organisational cultures can be an organizing as well as a controlling mechanism for organisations. And finally, organisational culture consists of three levels: assumptions, which are below the surface, values, and artifacts.

Exercises

- Why do companies need culture?

- Give an example of an aspect of company culture that is a strength and one that is a weakness.

- In what ways does culture serve as a controlling mechanism?

- If assumptions are below the surface, why do they matter?

- Share examples of artifacts you have noticed at different organisations.

Characteristics of Organizational Culture

Dimensions of Culture

Which values characterize an organization’s culture? Even though culture may not be immediately observable, identifying a set of values that might be used to describe an organization’s culture helps us identify, measure, and manage culture more effectively. For this purpose, several researchers have proposed various culture typologies. One typology that has received a lot of research attention is the organizational culture profile (OCP), in which culture is represented by seven distinct values (Chatman & Jehn, 1991; O’Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell, 1991). We will describe the OCP as well as two additional dimensions of organizational culture that are not represented in that framework but are important dimensions to consider: service culture and safety culture.

Innovative Cultures

According to the OCP framework, companies that have innovative cultures are flexible and adaptable, and experiment with new ideas. These companies are characterized by a flat hierarchy in which titles and other status distinctions tend to be downplayed.

W. L. Gore & Associates has made its name by creating innovative, technology-driven solutions, from medical devices that treat aneurysms to high-performance GORE‑TEX fabrics. A privately held company whose annual sales exceed $2.5 billion, Gore is committed to perpetuating its more than 50-year tradition of product innovation. Gore focuses its efforts in four main areas: electronics, fabrics, industrial and medical products. Gore’s fabrics provide protection from the elements and enable wearers to remain comfortable across a broad range of activities and conditions.

Gore is as well known for its unique corporate culture as it is for its innovative products. The company uses a team-based environment that encourages personal initiative and person-to-person communication among all “associates,” as employees are known. Gore’s emphasis on minimal barriers to creativity and sound decision making has proved to be good business. The company has earned a reputation for integrity and ethical practices, a reputation reinforced by its unwavering commitment to product performance and reliability. By encouraging individual initiative and innovation, the corporate culture fosters both product success and associate satisfaction. Today Gore is one of only four companies to appear in every listing of the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America,” now published annually in Fortune magazine. The company also ranks consistently among the “Best Companies to Work For” in the U.K., Germany, Italy and France.

Aggressive Cultures

In an article of the New York Times dated February 22, 2017, it was written that when new employees join Uber, they are asked to subscribe to 14 core company values, including making bold bets, being “obsessed” with the customer, and “always be hustlin’.” The ride-hailing service particularly emphasizes “meritocracy,” the idea that the best and brightest will rise to the top based on their efforts, even if it means stepping on toes to get there.

Those values have helped propel Uber to one of Silicon Valley’s biggest success stories.

Yet the focus on pushing for the best result has also fueled what current and former Uber employees describe as an environment in which workers are sometimes pitted against one another and where a blind eye is turned to infractions from top performers.

Interviews with more than 30 current and former Uber employees, as well as reviews of internal emails, chat logs and tape-recorded meetings, paint a picture of an often unrestrained workplace culture. Among the most egregious accusations from employees, who either witnessed or were subject to incidents and who asked to remain anonymous because of confidentiality agreements and fear of retaliation: One Uber manager groped female co-workers’ breasts at a company retreat in Las Vegas. A director shouted a homophobic slur at a subordinate during a heated confrontation in a meeting. Another manager threatened to beat an underperforming employee’s head in with a baseball bat.

Susan Fowler, an engineer who left Uber in December 2016, published a blog post about her time at the company. She detailed a history of discrimination and sexual harassment by her managers, which she said was shrugged off by Uber’s human resources department. Ms. Fowler said the culture was stoked — and even fostered — by those at the top of the company.

“It seemed like every manager was fighting their peers and attempting to undermine their direct supervisor so that they could have their direct supervisor’s job,” Ms. Fowler wrote. “No attempts were made by these managers to hide what they were doing: They boasted about it in meetings, told their direct reports about it, and the like.”

Outcome-Oriented Cultures

The OCP framework describes outcome-oriented cultures as those that emphasize achievement, results, and action as important values. A good example of an outcome-oriented culture may be Best Buy Co. Inc.

Best Buy (BB) is continually redefining the norms of how their business operates. Here is one such example of tech innovation during the pandemic

At the beginning of the pandemic, it was incredibly important for BB to quickly understand how their customers’ needs for technology were changing, especially as people across the country had to immediately begin working and learning from home. BB also needed to quickly figure out how to engage with them safely and reliably, in an uncertain and rapidly changing environment.

Within just a couple of days BB implemented new technology that allowed their stores to continue supporting their customers’ essential tech needs in the safest ways possible, both for them and for their employees. That included offering contactless curbside pickup and the ability for store employees to conduct virtual consultations with customers. BB also quickly built out capabilities within our employee app that allowed for COVID-19 health screenings prior to employees’ shifts.

BB has leant how crucial it is for them to quickly adapt to their customer’s pressing technology needs, and have shifted to a “digital-first” mindset. Their teams are helping the company figure out where they can leverage tech and data science, so BB can quickly create breakthrough experiences, enable better ways to help customers and speed up how they test, learn and solve complex problems.

Outcome-oriented cultures hold employees as well as managers accountable for success and utilize systems that reward employee and group output. In these companies, it is more common to see rewards tied to performance indicators as opposed to seniority or loyalty. Research indicates that organizations that have a performance-oriented culture tend to outperform companies that are lacking such a culture (Nohria, Joyce, & Roberson, 2003). At the same time, some outcome-oriented companies may have such a high drive for outcomes and measurable performance objectives that they may suffer negative consequences. Companies over-rewarding employee performance such as Enron Corporation and WorldCom experienced well-publicized business and ethical failures. When performance pressures lead to a culture where unethical behaviours become the norm, individuals see their peers as rivals and short-term results are rewarded; the resulting unhealthy work environment serves as a liability (Probst & Raisch, 2005).

Stable Cultures

Stable cultures are predictable, rule-oriented, and bureaucratic. These organizations aim to coordinate and align individual effort for greatest levels of efficiency. When the environment is stable and certain, these cultures may help the organization be effective by providing stable and constant levels of output (Westrum, 2004). These cultures prevent quick action, and as a result may be a misfit to a changing and dynamic environment. Public sector institutions may be viewed as stable cultures. In the private sector, Kraft Foods Inc. is an example of a company with centralized decision making and rule orientation that suffered as a result of the culture-environment mismatch (Thompson, 2006). Its bureaucratic culture is blamed for killing good ideas in early stages and preventing the company from innovating. When the company started a change program to increase the agility of its culture, one of their first actions was to fight bureaucracy with more bureaucracy: they created the new position of VP of business process simplification, which was later eliminated (Boyle, 2004; Thompson, 2005; Thompson, 2006).

People-Oriented Cultures

People-oriented cultures value fairness, supportiveness, and respect for individual rights. These organizations truly live the mantra that “people are their greatest asset.” In addition to having fair procedures and management styles, these companies create an atmosphere where work is fun and employees do not feel required to choose between work and other aspects of their lives. In these organizations, there is a greater emphasis on and expectation of treating people with respect and dignity (Erdogan, Liden, & Kraimer, 2006). One study of new employees in accounting companies found that employees, on average, stayed 14 months longer in companies with people-oriented cultures (Sheridan, 1992).

Southwest Airlines’ culture is woven into all aspects of the company, from business performance to employee happiness. The airline puts employees first; this tribal type of company culture promotes strong relationships among colleagues.

Three crucial elements define Southwest Airlines’ company culture: appreciation, recognition, and celebration.

A decade or so ago, the company decided to formalize its workplace culture by identifying six core values and creating a Culture Services department.

Southwest Airlines has many rituals to bring its values to life and celebrate each other. One of the most significant is “Culture Blitzes” in which a team visits an airport, touching every Southwest employee with food, fun, and support. The team even cleans the planes, allowing the crew to leave as soon as they land.

The company’s logo is a heart and employees believe that ” without a heart, the plane is just a machine”.

Team-Oriented Cultures

Companies with team-oriented cultures are collaborative and emphasize cooperation among employees.

Slack’s company culture is a vivid metaphor of its own product. The company acts as an excellent collaboration hub, embracing an open by default communication approach. Rather than choose specific channels, Slack’s CEO wants communications to be transparent, so everyone knows what’s going on and are able to provide solutions.

At Slack, people work hard and go home. The company culture understands that people have lives – they expect high performance and total dedication, but only during regular working hours. Funnily enough, employees are forbidden to use the Slack app after 6 pm or during the weekend.

The power of words plays a crucial role in Slack culture. Employees are encouraged to speak well and with purpose. There’s an obsession with continually improving communication – both their own and their clients’.

A strong sense of community is essential to Slack’s powerful company culture. Empathy is vital to not only understanding the end user, but also their colleagues. Slack promotes diversity and recruits people with diverse backgrounds and voices. Everyone has an obligation to contribute and make things better.

Detail-Oriented Cultures

Organizations with detail-oriented cultures are characterized in the OCP framework as emphasizing precision and paying attention to details. Such a culture gives a competitive advantage to companies in the hospitality industry by helping them differentiate themselves from others.

How much would you empower your employees to serve your customers? The Ritz-Carlton has put a number to that very question.

The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, LLC is an American multinational company that operates the luxury hotel chain known as The Ritz-Carlton. The company has 108 luxury hotels and resorts in 30 countries and territories with 29,158 rooms,

If you’re one of their customers, the good news is that…The Ritz-Carlton Will Spend $2,000 To Make You Happy. The Ritz empowers its employees to spend up to $2,000 to solve customer problems without asking for a manager.

The real point of the $2000 of discretion, as Ritz-Carlton president and COO Herve Humler explains, is as a tool to empower and encourage employees to use their time, effort and –when needed–the company’s money to enhance the experience of any guest– even a guest who is already having a blast! It’s an approach that’s not just about solving problems but about finding opportunities.

The hotel keeps records of all customer requests, such as which newspaper the guest prefers or what type of pillow the customer uses. This information is put into a computer system and used to provide better service to returning customers. Any requests hotel employees receive, as well as overhear, might be entered into the database to serve customers better. The hotel knows that in the long run they will be rewarded with loyalty and that the customer relationship they will preserve is worth far more than any individual transaction.

Service Culture

Service culture is not one of the dimensions of OCP, but given the importance of the retail industry in the overall economy, having a service culture can make or break an organization. Some of the organizations we have illustrated in this section, such as Nordstrom, Southwest Airlines and the Ritz-Carlton are famous for their service culture. In these organizations, employees are trained to serve the customer well, and cross-training is the norm. Employees are empowered to resolve customer problems in ways they see fit. Because employees with direct customer contact are in the best position to resolve any issues, employee empowerment is truly valued in these companies. For example, Umpqua Bank, operating in the northwestern United States, is known for its service culture. All employees are trained in all tasks to enable any employee to help customers when needed. Branch employees may come up with unique ways in which they serve customers better, such as opening their lobby for community events or keeping bowls full of water for customers’ pets. The branches feature coffee for customers, Internet kiosks, and withdrawn funds are given on a tray along with a piece of chocolate. They also reward employee service performance through bonuses and incentives (Conley, 2005; Kuehner-Herbert, 2003).

Safety Culture

Simply put, an organization’s workplace safety culture (sometimes called “safety climate”) describes the values, priorities, beliefs, and ideals individual members of that organization express relating to staying safe, as well as how those ideas propagate throughout the organization.

In organizations where safety-sensitive jobs are performed, creating and maintaining a safety culture provides a competitive advantage because the organization can reduce accidents, maintain high levels of morale and employee retention, and increase profitability by cutting workers’ compensation insurance costs.

Mark French, Dalkia Energy Solutions, says: “Dalkia uses the term “zero harm” to describe their safety efforts. It is a wonderful phrase that sums up what I feel my goal is as a safety professional. The real mission is to prevent any harm to my team, to the environment, and to the clients and communities that we service. Dalkia has a distinct focus on culture, not just on safety. It is a culture that is focused on people which means empowerment, inclusion, and a safe place to work.”

Matt McMahan, Texas Roadhouse, emphasizes the importance of adapting to the given situation: “The meaning of safety culture will differ depending on the circumstances. When referring to operational safety, it can mean daily awareness and frequent communication. In terms of safety management, the signs of a safety culture can mean the attention around identifying and determining appropriate treatment for the identified risks.”

Some companies suffer severe consequences when they are unable to develop such a culture.

Strength of Culture

A strong culture is one that is shared by organizational members (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987; Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003). In other words, if most employees in the organization show consensus regarding the values of the company, it is possible to talk about the existence of a strong culture. A culture’s content is more likely to affect the way employees think and behave when the culture in question is strong. For example, cultural values emphasizing customer service will lead to higher quality customer service if there is widespread agreement among employees on the importance of customer service related values (Schneider, Salvaggio, & Subirats, 2002).

Building a strong, agile company culture has contributed to Spotify’s rapid growth. Its experiment-friendly culture with an emphasis on test-and-learn and mistake-tolerance has become the paradigm for many to follow.

One of the clues lies in balancing employee autonomy and accountability. Spotify’s approach starts by aligning employees around one shared purpose and allowing teams to discover their own way to get there. This requires providing freedom for experimentation, balancing alignment with control, and autonomous team structures that are fully accountable..

At Spotify, flexibility is not about what people want, but about being more mindful of their choices. For example, take the “pull the plug” norm. While executives in most companies keep pushing projects even if they lack traction, Spotify employees are data-informed – when they don’t see the expected results, people can pull the plug.

Spotify employees are encouraged to break the rules with a purpose. If something works, they keep it; otherwise, they dump it. Context matters too. Spotify culture works under the premise that “What works well in most places, may not work in your environment.”

It is important to realize that a strong culture may act as an asset or liability for the organization, depending on the types of values that are shared. For example, imagine a company with a culture that is strongly outcome oriented. If this value system matches the organizational environment, the company outperforms its competitors. On the other hand, a strong outcome-oriented culture coupled with unethical behaviours and an obsession with quantitative performance indicators may be detrimental to an organization’s effectiveness. An extreme example of this dysfunctional type of strong culture is Enron.

A strong culture may sometimes outperform a weak culture because of the consistency of expectations. In a strong culture, members know what is expected of them, and the culture serves as an effective control mechanism on member behaviours. Research shows that strong cultures lead to more stable corporate performance in stable environments. However, in volatile environments, the advantages of culture strength disappear (Sorensen, 2002).

One limitation of a strong culture is the difficulty of changing a strong culture. If an organization with widely shared beliefs decides to adopt a different set of values, unlearning the old values and learning the new ones will be a challenge, because employees will need to adopt new ways of thinking, behaving, and responding to critical events. For example, the Home Depot Inc. had a decentralized, autonomous culture where many business decisions were made using “gut feeling” while ignoring the available data. When Robert Nardelli became CEO of the company in 2000, he decided to change its culture, starting with centralizing many of the decisions that were previously left to individual stores. This initiative met with substantial resistance, and many high-level employees left during his first year. Despite getting financial results such as doubling the sales of the company, many of the changes he made were criticized. He left the company in January 2007 (Charan, 2006; Herman & Wernle, 2007).

A strong culture may also be a liability during a merger. During mergers and acquisitions, companies inevitably experience a clash of cultures, as well as a clash of structures and operating systems. Culture clash becomes more problematic if both parties have unique and strong cultures.

Do Organizations Have a Single Culture?

So far, we have assumed that a company has a single dominant culture that is shared throughout the organization. However, you may have realized that this is an oversimplification. In reality there might be multiple cultures within any given organization. For example, people working on the sales floor may experience a different culture from that experienced by people working in the warehouse. The Marketing team formed by extrovert personalities represent a different subculture from those in Finance or Accounting teams. A culture that emerges within different departments, branches, or geographic locations is called a subculture. Subcultures may arise from the personal characteristics of employees and managers, as well as the different conditions under which work is performed.

A subculture can function quite well within the dominant culture.

Counterculture groups are also smaller groups of like-minded people who gather within a more dominant culture. However, different from a subculture, a countercultural group goes against the mainstream dominant culture. In fact, the key difference between a counterculture movement and subculture is the strong desire to change the dominant culture. These groups are created to fight against the pervasive values of a larger culture. They are formed around interests, dislikes, and disdain. Google’s employees formed a counterculture to resist participating in the making of drones for the United States armed forces. They said that it goes against the company’s values of “Don’t be evil”

Exercises

- Think about an organisation you are familiar with. Based on the dimensions of OCP, how would you characterize its culture?

- Out of the culture dimensions described, which dimension do you think would lead to higher levels of employee satisfaction and retention? Which one would be related to company performance?

- What are the pros and cons of an outcome-oriented culture?

- When bureaucracies were first invented they were considered quite innovative. Do you think that different cultures are more or less effective at different points in time and in different industries? Why or why not?

- Can you imagine an effective use of subcultures within an organisation?