5.1 What is Leadership?

Leadership may be defined as the act of influencing others to work toward a goal. Leaders exist at all levels of an organization. Some leaders hold a position of authority and may utilize the power that comes from their position, as well as their personal power to influence others. They are called formal leaders. In contrast, informal leaders are without a formal position of authority within the organization but demonstrate leadership by influencing others through personal forms of power. One caveat is important here: leaders do not rely on the use of force to influence people. Instead, people willingly adopt the leader’s goal as their own goal. If a person is relying on force and punishment, the person is a dictator, not a leader.

What makes leaders effective? What distinguishes people who are perceived as leaders from those who are not perceived as leaders? More importantly, how do we train future leaders and improve our own leadership ability? These are important questions that have attracted scholarly attention in the past several decades. In this chapter, we will review the history of leadership studies and summarize the major findings relating to these important questions. Around the world, we view leaders as at least partly responsible for their team or company’s success and failure. Company CEOs are paid millions of dollars in salaries and stock options with the assumption that they hold their company’s future in their hands. In politics, education, sports, profit and nonprofit sectors, the influence of leaders over the behaviours of individuals and organizations is rarely questioned. When people and organizations fail, managers and CEOs are often viewed as responsible. Some people criticize the assumption that leadership always matters and call this belief “the romance of leadership.” However, research evidence pointing to the importance of leaders for organizational success is accumulating (Hogan, Curphy, & Hogan, 1994).

Who is a Leader? Trait Approaches to Leadership

The earliest approach to the study of leadership sought to identify a set of traits that distinguished leaders from non-leaders. What were the personality characteristics and the physical and psychological attributes of people who are viewed as leaders? Because of the problems in measurement of personality traits at the time, different studies used different measures. By 1940, researchers concluded that the search for leadership-defining traits was futile. In recent years, though, after the advances in personality literature such as the development of the Big Five personality framework, researchers have had more success in identifying traits that predict leadership (House & Aditya, 1997). Most importantly, charismatic leadership, which is among the contemporary approaches to leadership, may be viewed as an example of a trait approach.

The traits that show relatively strong relations with leadership are discussed below (Judge et al., 2002).

Intelligence

General mental ability, which psychologists refer to as “g” and which is often called “IQ” in everyday language, has been related to a person’s emergence as a leader within a group. Specifically, people who have high mental abilities are more likely to be viewed as leaders in their environment (House & Aditya, 1997; Ilies, Gerhardt, & Huy, 2004; Lord, De Vader, & Alliger, 1986; Taggar, Hackett, & Saha, 1999). We should caution, though, that intelligence is a positive but modest predictor of leadership, and when actual intelligence is measured with paper-and-pencil tests, its relationship to leadership is a bit weaker compared to when intelligence is defined as the perceived intelligence of a leader (Judge, Colbert, & Ilies, 2004). In addition to having a high IQ, effective leaders tend to have high emotional intelligence (EQ). People with high EQ demonstrate a high level of self-awareness, motivation, empathy, and social skills. The psychologist who coined the term emotional intelligence, Daniel Goleman, believes that IQ is a threshold quality: It matters for entry to high-level management jobs, but once you get there, it no longer helps leaders because most leaders already have a high IQ. According to Goleman, what differentiates effective leaders from ineffective ones becomes their ability to control their own emotions and understand other people’s emotions, their internal motivation, and their social skills (Goleman, 2004).

Big 5 Personality Traits

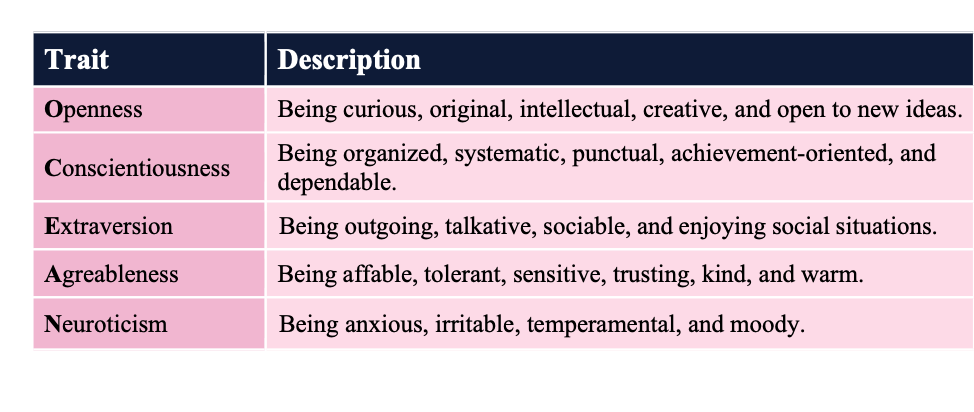

Psychologists have proposed various systems for categorizing the characteristics that make up an individual’s unique personality; one of the most widely accepted is the “Big Five” model, which rates an individual according to Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Several of the Big Five personality traits have been related to leadership emergence (whether someone is viewed as a leader by others) and effectiveness (Judge et al., 2002).

For example, extraversion is related to leadership. Extraverts are sociable, assertive, and energetic people. They enjoy interacting with others in their environment and demonstrate self-confidence. Because they are both dominant and sociable in their environment, they emerge as leaders in a wide variety of situations. Out of all personality traits, extraversion has the strongest relationship with both leader emergence and leader effectiveness. This is not to say that all effective leaders are extraverts, but you are more likely to find extraverts in leadership positions. An example of an introverted leader is Jim Buckmaster, the CEO of Craigslist. He is known as an introvert, and he admits to not having meetings because he does not like them (Buckmaster, 2008). Research shows that another personality trait related to leadership is conscientiousness. Conscientious people are organized, take initiative, and demonstrate persistence in their endeavors. Conscientious people are more likely to emerge as leaders and be effective in that role. Finally, people who have openness to experience—those who demonstrate originality, creativity, and are open to trying new things—tend to emerge as leaders and also be quite effective.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is not one of the Big Five personality traits, but it is an important aspect of one’s personality. The degree to which a person is at peace with oneself and has an overall positive assessment of one’s self worth and capabilities seem to be relevant to whether someone is viewed as a leader. Leaders with high self-esteem support their subordinates more and, when punishment is administered, they punish more effectively (Atwater et al., 1998; Niebuhr, 1984).

It is possible that those with high self-esteem have greater levels of self-confidence and this affects their image in the eyes of their followers. Self-esteem may also explain the relationship between some physical attributes and leader emergence. For example, research shows a strong relationship between being tall and being viewed as a leader (as well as one’s career success over life). It is proposed that self-esteem may be the key mechanism linking height to being viewed as a leader because people who are taller are also found to have higher self-esteem and therefore may project greater levels of charisma as well as confidence to their followers (Judge & Cable, 2004).

Integrity

Research also shows that people who are effective as leaders tend to have a moral compass and demonstrate honesty and integrity (Reave, 2005). Leaders whose integrity is questioned lose their trustworthiness, and they hurt their company’s business along the way. For example, when it was revealed that Whole Foods Market CEO, John Mackey, was using a pseudonym to make negative comments online about the company’s rival Wild Oats Markets Inc., his actions were heavily criticized, his leadership was questioned, and the company’s reputation was affected (Farrell & Davidson, 2007).

There are also some traits that are negatively related to leader emergence and being successful in that position. For example, agreeable people who are modest, good natured, and avoid conflict are less likely to be perceived as leaders (Judge et al., 2002).

Despite problems in trait approaches, these findings can still be useful to managers and companies. For example, knowing about leadership traits helps organizations select the right people into positions of responsibility. The key to benefiting from the findings of trait researchers is to be aware that not all traits are equally effective in predicting leadership potential across all circumstances. Some organizational situations allow leader traits to make a greater difference (House & Aditya, 1997). For example, in small, entrepreneurial organizations where leaders have a lot of leeway to determine their own behaviour, the type of traits leaders have may make a difference in leadership potential. In large, bureaucratic, and rule-bound organizations such as the government and the military, a leader’s traits may have less to do with how the person behaves and whether the person is a successful leader (Judge et al., 2002). Moreover, some traits become relevant in specific circumstances. For example, bravery is likely to be a key characteristic in military leaders, but not necessarily in business leaders. Scholars now conclude that instead of trying to identify a few traits that distinguish leaders from non-leaders, it is important to identify the conditions under which different traits affect a leader’s performance, as well as whether a person emerges as a leader (Hackman & Wageman, 2007).

Key Takeaways

Many studies searched for a limited set of personal attributes, or traits, which would make someone be viewed as a leader and be successful as a leader. Some traits that are consistently related to leadership include intelligence (both mental ability and emotional intelligence), personality (extraversion, conscientiousness, openness to experience, self-esteem), and integrity. The main limitation of the trait approach was that it ignored the situation in which leadership occurred. Therefore, it is more useful to specify the conditions under which different traits are needed.

Exercises

- Think of a leader you admire. What traits does this person have? Are they consistent with the 6 traits discussed in this chapter? If not, why is this person effective despite the presence of different traits?

- Can the findings of trait approaches be used to train potential leaders? Which traits seem easier to teach? Which are more stable

- How can organisations identify future leaders with a given set of traits? Which methods would be useful for this purpose?

- What other traits can you think of that would be relevant to leadership?

What Do Leaders Do? Behavioural Approaches to Leadership

Leader Behaviours

When trait researchers became disillusioned in the 1940s, their attention turned to studying leader behaviours. What did effective leaders actually do? Which behaviours made them perceived as leaders? Which behaviours increased their success? To answer these questions, researchers at Ohio State University and the University of Michigan used many different techniques, such as observing leaders in laboratory settings as well as surveying them. This research stream led to the discovery of two broad categories of behaviours: task-oriented behaviours (sometimes called initiating structure) and people-oriented behaviours (also called consideration). Task-oriented leader behaviours involve structuring the roles of subordinates, providing them with instructions, and behaving in ways that will increase the performance of the group. Task-oriented behaviours are directives given to employees to get things done and to ensure that organizational goals are met. People-oriented leader behaviours include showing concern for employee feelings and treating employees with respect. People-oriented leaders genuinely care about the wellbeing of their employees, and they demonstrate their concern in their actions and decisions. At the time, researchers thought that these two categories of behaviours were the keys to the puzzle of leadership (House & Aditya, 1997). However, research did not support the argument that demonstrating both of these behaviours would necessarily make leaders effective (Nystrom, 1978).

When we look at the overall findings regarding these leadership behaviours, it seems that both types of behaviours, in the aggregate, are beneficial to organizations, but for different purposes. For example, when leaders demonstrate people-oriented behaviours, employees tend to be more satisfied and react more positively. However, when leaders are task oriented, productivity tends to be a bit higher (Judge, Piccolo, & Ilies, 2004). Moreover, the situation in which these behaviours are demonstrated seems to matter. In small companies, task-oriented behaviours were found to be more effective than in large companies (Miles & Petty, 1977). There is also some evidence that very high levels of leader task-oriented behaviours may cause burnout with employees (Seltzer & Numerof, 1988).

Leader Decision Making

Another question behavioural researchers focused on involved how leaders actually make decisions and the influence of decision-making styles on leader effectiveness and employee reactions. Three types of decision-making styles were studied. In authoritarian decision making, leaders make the decision alone without necessarily involving employees in the decision-making process. When leaders use democratic decision making, employees participate in the making of the decision. Finally, leaders using laissez-faire decision making leave employees alone to make the decision. The leader provides minimum guidance and involvement in the decision.

As with other lines of research on leadership, these studies did not identify one decision-making style as the best. It seems that the effectiveness of the style the leader is using depends on the circumstances. A review of the literature shows that when leaders use more democratic or participative decision-making styles, employees tend to be more satisfied; however, the effects on decision quality or employee productivity are weaker. Moreover, instead of expecting to be involved in every single decision, employees seem to care more about the overall prescriptiveness of the organizational climate (Miller & Monge, 1986). Different types of employees may also expect different levels of involvement. In a research organization, scientists viewed democratic leadership most favorably and authoritarian leadership least favorably (Baumgartel, 1957), but employees working in large groups where opportunities for member interaction was limited preferred authoritarian leader decision making (Vroom & Mann, 1960). Finally, the effectiveness of each style seems to depend on who is using it. There are examples of effective leaders using both authoritarian and democratic styles. At Hyundai Motor America, high-level managers use authoritarian decision-making styles, and the company is performing very well (Deutschman, 2004; Welch, Kiley, & Ihlwan, 2008).

The track record of the laissez-faire decision-making style is more problematic. Research shows that this style is negatively related to employee satisfaction with leaders and leader effectiveness (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). Laissez-faire leaders create high levels of ambiguity about job expectations on the part of employees, and employees also engage in higher levels of conflict when leaders are using the laissez- faire style (Skogstad et al., 2007).

Exercises

- Give an example of a leader you admire whose behaviour is primarily task oriented, and one whose behaviour is primarily people oriented.

- What are the limitations of authoritarian decision making? Under which conditions do you think authoritarian style would be more effective?

- What are the limitations of democratic decision making? Under which conditions do you think democratic style would be more effective?

- What are the limitations of laissez-faire decision making? Under which conditions do you think laissez-faire style would be more effective?

- Examine your own leadership style. Which behaviours are you more likely to demonstrate? Which decision-making style are you more likely to use?

Mini Case Scenario

START OF SEASON

LEADERSHIP STYLE SETS A TONE

You have just been promoted to be the manager of a rafting company that you have worked for over the last three summers. As a guide, the biggest problem you see is that many guides show up to start their work day at 9:30 rather than the 9 a.m. start time. When guides show up late, the work to prepare the rafts falls to two few people and it causes delays to the start of the day’s activities. You decide that you are going to start the year off by addressing this issue. Your message is, “Lateness will not be tolerated and guides will be terminated for being more than 30 minutes late.” You clearly communicate this work rule to all guides during their one-day training session, held a week before the summer season begins.

The night before the first day of opening, all the retuning raft captains have a big party on the beach. As you are expecting a large group of 200 students from Montreal to arrive at the site the next day, you remind all guides before the party that the start time the next day is 9 a.m. and everybody needs to be ready to launch the rafts on time. Ten guides are scheduled to start at 9 a.m. the next day.

At 9 a.m., nine guides appear, ready for the day. David, a veteran guide and one of the best, does not show until 9:32.

You have two options: 1) terminate David or, 2) reprimand David. What option should you choose? How do you justify your decision?

The Twist

The guides get together and inform you that that all of them will be calling in sick the next day, just when another large group is coming in. The guides have been complaining that your leadership style is creating an unfriendly and hostile workplace.

What do you do? What have you learned from this experience?

© Ted Rogers Leadership Centre. This case is made available for public use under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivs (CC BY-NC-ND) license.